Case Western Reserve University Faculty Join Celebration for 25th Anniversary of Cystic Fibrosis Gene Discovery

Case Western Reserve University faculty and clinicians are among those this weekend commemorating the discovery 25 years ago of the transmembrane conductance Cystic Fibrosis gene (CFTR) and reflecting on subsequent treatment advances that stemmed from the genetic breakthrough a quarter-century ago.

The discovery was acheived in 1989 by a multi-institutional team of researchers based at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada, and led by Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui. Not only did Dr. Tsui’s watershed discovery of the gene that causes cystic fibrosis impact lives of children and young adults with CF, it also paved the way for what is now known as individualized medicine. CFTR was the first disease-causing gene to be identified and at the time of its discovery touted as one of the most significant advances in the history of human genetics. It is now understood to be one of the most significant breakthroughs in human genetics in 50 years, for which Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame in 2012.

The discovery was acheived in 1989 by a multi-institutional team of researchers based at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada, and led by Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui. Not only did Dr. Tsui’s watershed discovery of the gene that causes cystic fibrosis impact lives of children and young adults with CF, it also paved the way for what is now known as individualized medicine. CFTR was the first disease-causing gene to be identified and at the time of its discovery touted as one of the most significant advances in the history of human genetics. It is now understood to be one of the most significant breakthroughs in human genetics in 50 years, for which Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame in 2012.

After the CF gene discovery in 1989, Dr. Tsui set up a mutation database that would house the collection of mutations in the CF gene so researchers around the world could benefit from the most up-to-date genetic information about the disease. This database remains a major resource for clinical and basic research and serves as a model for other genetic disease databases. In total, there are over 1,900 mutations in the CF gene. Scientists have learned that many of these can be classified with respect to the type of defect they cause in the protein. Gaining this understanding has driven the race to find mutation-targeted therapeutics.

After the CF gene discovery in 1989, Dr. Tsui set up a mutation database that would house the collection of mutations in the CF gene so researchers around the world could benefit from the most up-to-date genetic information about the disease. This database remains a major resource for clinical and basic research and serves as a model for other genetic disease databases. In total, there are over 1,900 mutations in the CF gene. Scientists have learned that many of these can be classified with respect to the type of defect they cause in the protein. Gaining this understanding has driven the race to find mutation-targeted therapeutics.

Now, on the 25th anniversary of the discovery of the CFTR gene, more than two-dozen CF innovators and clinicians, including five from the Case Western Reserve University campus took this special occasion to reflect on the discovery and the status of research and treatment during videotaped interviews.

Portions of these interviews with physicians, scientists, patients and families will appear beginning Friday, Oct. 10, at a special satellite symposium, Ahead of the Curve: CFTR at 25, during the 28th Annual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference at the Georgia World Congress Center in Atlanta.

[adrotate group=”1″]

The satellite symposium will be presented by continuing education firm DKBmed, LLC, in collaboration with Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and The Institute for Johns Hopkins Nursing. All two-dozen interviews conducted this past summer for CFTR at 25 may be accessed online in late October at cftr25 or on YouTube’s eCysticFibrosis Review Channel.

Two of the interviewed Case Western Reserve School of Medicine faculty members played pioneering roles in cystic fibrosis research during the past 25 years. Pamela B. Davis, MD, PhD, dean and senior vice president for medical affairs, served as director of the Adult Cystic Fibrosis Program at University Hospitals Case Medical Center before assuming duties as dean.

Dean Davis is the principal investigator for the school’s $64.6 million Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program,and also a prolific researcher whose work focuses largely on cystic fibrosis. She has published with more than 130 articles in peer review journals, and has continuously funded by the NIH for more than three decades. She holds seven U.S. patents and is a founding scientist of Copernicus Therapeutics Inc., a biotechnology company that creates novel pharmaceutical targeting and delivery systems. Dr. Davis has served in prominent roles such as the Advisory Council to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Board of Scientific Counselors for the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Dean Davis is the principal investigator for the school’s $64.6 million Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program,and also a prolific researcher whose work focuses largely on cystic fibrosis. She has published with more than 130 articles in peer review journals, and has continuously funded by the NIH for more than three decades. She holds seven U.S. patents and is a founding scientist of Copernicus Therapeutics Inc., a biotechnology company that creates novel pharmaceutical targeting and delivery systems. Dr. Davis has served in prominent roles such as the Advisory Council to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and the Board of Scientific Counselors for the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Dr. Davis has also been a recipient of the Paul Di SantAgnese Award from the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, the Rosenthal Prize for academic pediatrics, the Smith College Medal, and has regularly been named in “Best Doctors in America” and “Top Doctors.” She also has been elected to the Association of American Physicians, and inducted into the Cleveland Medical Hall of Fame and the Ohio Womens Hall of Fame.

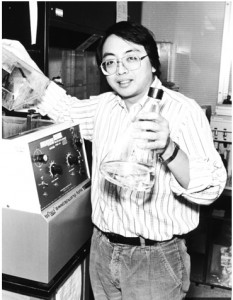

Mitchell Drumm, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and genetics and genome sciences, participated in the CFTR gene discovery process during his graduate studies at the University of Michigan.

Mitchell Drumm, PhD, a professor of pediatrics and genetics and genome sciences, participated in the CFTR gene discovery process during his graduate studies at the University of Michigan.

Dr. Drumm’s research focuses on the genetics of cystic fibrosis (CF), specifically with the goal of identifying therapeutic targets for the treatment of CF. His interest in CF began with his thesis work to develop a technique, termed “chromosome jumping” to rapidly move from one position in the genome to another on the same chromosome. The project evolved into identifying the location of the gene causing CF, and culminated in the discovery and cloning of the CFTR gene. Since that time, he has worked to understand how CFTR works at the cellular and tissue level, and more currently how the various tissues and organs interact to create the spectrum of traits associated with the disease. At the molecular level, his lab has investigating the promoter of the CFTR gene, as its regulation may be tied to the regulation of other genes, which may in turn contribute to the disease.

Dr. Drumm worked as a young scientist in the late 1980s in the lab of Francis Collins, MD, PhD, who then led genetics research at the University of Michigan — specifically on chromosome jumping, a cutting-edge technology at the time, to discover genes for which Dr. Collins had gained fame in the mid-1980s. It was an approach that led Dr. Collins to identify the CFTR gene in collaboration with Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui and John Riordan, Ph.D., at the Toronto Hospital for Sick Children. (Dr. Collins became director of NIH two decades later.)

“With the CFTR discovery, the original thought was to fix the gene and replace it,” Dr. Drumm explains. “But we have since found that our methods to repair the gene were insufficient to trigger appropriate salt and water transport function that is faulty in cystic fibrosis. We have since discovered compounds that stimulate the salt and water transport channels, a finding that would not have occurred without the knowledge we gained from discovering the CFTR gene.”

Dr. Drumm’s lab has also returned to more classic genetic approaches to take advantage of the substantial variation in the course of disease between CF patients. Currently, Dr. Drumm and collaborators are examining genetic determinants of this variation. The rationale for these studies is that understanding the source of variation should suggest therapeutic targets for the disorder. To accomplish these goals, the Drumm lab is employing human and mouse genetics as complementing approaches. Using CF mice as a model, his laboratory is examining the heritability of traits believed to be involved in the pathophysiology of CF, such as epithelial ion transport and changes in the growth axis. Mouse genetics provide a powerful tool for identifying loci of interest, but clearly mice are a limited model of CF-relevant traits. Therefore, CF patients are also being studied by the Drumm laboratory and collaborators at the University of North Carolina, Johns Hopkins University and the University of Toronto in which they are investigating the role of common genetic variants across the genome to identify genes involved in the pathophysiology of the disease.

Dr. Drumm praises Case Western Reserve’s prominent role in the history of CF research and treatment. “We have such a unique environment here with MD clinicians and PhD bench scientists collaborating extensively on cystic fibrosis,” he says. “This is one of the few places with that kind of interaction to move discoveries to therapies.”

Others interviewed from the Case Western Reserve campus represented the perspective of clinicians actively involved in a wide spectrum of CF patient care and research: James Chmiel, MD, an associate professor of pediatric pulmonology and clinician-researcher of CF inflammation at the School of Medicine and clinical director of pediatric pulmonology at UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital; Colette Bucur, RN, nurse practitioner and research coordinator of CF clinical trials, and Terri Schindler, RD, nutritionist in CF care, both of UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

Others interviewed from the Case Western Reserve campus represented the perspective of clinicians actively involved in a wide spectrum of CF patient care and research: James Chmiel, MD, an associate professor of pediatric pulmonology and clinician-researcher of CF inflammation at the School of Medicine and clinical director of pediatric pulmonology at UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital; Colette Bucur, RN, nurse practitioner and research coordinator of CF clinical trials, and Terri Schindler, RD, nutritionist in CF care, both of UH Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital.

Additional interviews feature policymakers, leading educators and renowned researchers and clinicians from Johns Hopkins University, Stanford University, University of North Carolina, University of California San Diego, University of Wisconsin, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Course Director Peter J. Mogayzel Jr., MD, PhD, director of Johns Hopkins Cystic Fibrosis Center, selected interviewees based on their knowledge and experience to address CF research and advances in care.

Dr. Mogayzel has been Director of the Cystic Fibrosis Center since 2002, Dr. Mogayzel is a Fellow of American College of Chest Physicians and the American Academy of Pediatrics, and a member of several societies including the American Thoracic Society. His research interests include the regulatory properties of the CFTR gene, mucociliary clearance and development of new therapeutics for cystic fibrosis.

Dr. Mogayzel has been Director of the Cystic Fibrosis Center since 2002, Dr. Mogayzel is a Fellow of American College of Chest Physicians and the American Academy of Pediatrics, and a member of several societies including the American Thoracic Society. His research interests include the regulatory properties of the CFTR gene, mucociliary clearance and development of new therapeutics for cystic fibrosis.

Interviewed CF patients and their families also put a human face on this illness by sharing their experiences with the disease that causes thick and sticky mucus to build up in airways and block digestive tract passages. The CFTR gene controls movement of salt and water in and out of the body’s cells. A faulty, or mutated, CFTR gene does not make the protein necessary to control the salt and water transport function, which triggers the excess mucus leading to cystic fibrosis.

In the 1950s, children with the illness rarely lived long enough to attend elementary school. Now, thanks to advances in treatment, the median survival is about 37 years after diagnosis. There have been reports, however, of CF patients living into their 70s. “We believed, somewhat naively 25 years ago, that from the gene, a cascade of tremendous understanding about the pathobiology of the disease would take place and then a cure,” Dr. Davis says. “It turned out to be a complicated gene regulated by a number of factors.”

Dr. Davis credits unprecedented collaboration and cooperation nationally for creating imaginative grants that eventually led to identifying CFTRs specific functions and how those were regulated. This far-reaching collaboration involved key research laboratories, major drug companies, the academic sector, the private sector, government agencies, particularly NIH, and a very committed Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. For her part in the discovery process, Dr. Davis worked on the concept that inflammation independently contributed to the pathobiology of CF lung disease, and, over the years, has published peer-reviewed journal papers on CF.

“Even though it took a long time to develop the first CF drug, many additional good discoveries came out of research on the CFTR gene,” Dr. Davis points out. “I hope we can learn from this gene discovery experience about where the barriers were, and then for the next disease, we can make discoveries faster, better and cheaper.”

Founded in 1843, Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine is the largest medical research institution in Ohio, and is among the nation’s top medical schools for research funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Beginning as the Medical Department of Western Reserve College (and popularly known then as the Cleveland Medical College), the school moved into its first permanent home, in downtown Cleveland, in 1846. In 1915, a 20-acre site was secured for a medical center in University Circle, the current home of Case Western Reserve University, its School of Medicine, and two of the schools affiliated hospitals, University Hospitals of Cleveland and the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center. University Circle also is home to many of the country’s outstanding cultural and educational institutions.

The school was one of the first medical schools in the country to employ instructors devoted to full-time teaching and research. Six of the first seven women to receive medical degrees from accredited American medical schools graduated from Western Reserve College (as it was called then) between 1850 and 1856.

The School of Medicine is recognized throughout the international medical community for outstanding achievements in teaching. The School’s innovative and pioneering Western Reserve curriculum interweaves four themes — research and scholarship, clinical mastery, leadership, and civic professionalism — to prepare students for the practice of evidence-based medicine in the rapidly changing health care environment of the 21st century. Nine Nobel Laureates have been affiliated with the School of Medicine.

Annually, the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine trains more than 800 MD and MD/PhD students and ranks in the top 25 among U.S. research-oriented medical schools as designated by U.S. News & World Reports Guide to Graduate Education.

The School of Medicine’s primary affiliate is University Hospital’s Case Medical Center and is additionally affiliated with MetroHealth Medical Center, the Louis Stokes Cleveland Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, and the Cleveland Clinic, with which it established the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine of Case Western Reserve University in 2002

For more information, visit:

https://casemed.case.edu

Sources:

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

The Hospital for Sick Children

Canadian Medical Hall of Fame

Image Credits:

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

The Hospital for Sick Children

Canadian Medical Hall of Fame