What the Lung Transplant Evaluation Process is Really Like

Written by |

Last week I wrote about how lung transplantation isn’t the Boogeyman I once thought it was. After I had done my research, I finally considered being evaluated for a transplant. My doctors and I expected it to be at least a couple years before I’d need one, but an infection in my port-a-cath sent my body into septic shock and made the need for new lungs urgent. So, keep in mind that a transplant evaluation process is often slower than mine. Each transplant center also has its own process.

My CF doctor in Hawaii began calling transplant centers in June 2016 while I was still suffering septic shock. Center after center rejected me without even looking at my records because I was culturing mycobacterium abscessus (most centers won’t transplant when the patient has this), and my septic shock complicated things. There is such a thing as being “too sick” for transplantation. Other reasons for rejection are lack of social support, lack of financial means, weighing too little or much, etc. The University of California at San Francisco was the only center willing to take the risk with me — and it ultimately paid off!

The testing and informative period

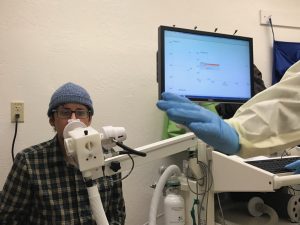

My Hawaii hospital ran tests on me to cut down the time needed for evaluation in San Francisco. These tests included CT scans, blood gas measurements, and pulmonary function tests. I arrived in San Francisco in September 2016 and began the official evaluation process. The program began by showing my family videos about the transplant process. This detailed rules, statistics, and details about the operation and recovery.

Rules included things like dietary restrictions, limitations on how far away from the hospital I could travel, how long I needed a caregiver to be with me after transplant and what their duties would be, and reasons I should call the team. They emphasize the toughness of recovery and how scary the surgery itself can be. They want to know you’re fully committed before devoting resources (including someone’s lungs) to you.

We entered three weeks of testing (not every day was used for this): six-minute walk tests, reflux tests, cardio tests, etc. Only a few tests were invasive, and they weren’t terrible. I also saw cardiology, infectious disease doctors, a CF team, and GI specialists during this time. Psychiatrists tested my mental health to assess if I was ready for the process or would need extra help to get along. Social workers also made sure I would have emotional and physical support from my caregivers. My parents (caregivers) signed a contract saying they would take care of me for months after transplant.

Lung allocation score and waiting

Once testing was done, the transplant team had private meetings about if they would accept me into the program. I was accepted onto the lung transplant waiting list in December. I was given a Lung Allocation Score (LAS), which assigns points based on test results. The higher the LAS (so, the lower the PFTs, walking test results, etc.), the higher the patient is on the list. Doctors give only the score they feel is necessary — if healthy enough to go years without a transplant, a patient’s LAS will be low. The likelihood of finding a donor match also is based on blood type.

My blood type, B-negative, is not super common. I received a LAS of 36 and, combined with my blood type, was supposed to wait on the list for lungs for an estimated five to nine months. I had to stay within three hours of the hospital at all times while listed and keep my phone close to me. They could call at any minute!

The surgery and recovery

I got lucky and had my transplant five weeks later. Honestly, the surgery was easier than I expected. I woke up with barely any pain; they put an epidural pain blocker in my spine. The transplant team wanted the pain nearly non-existent so I could get up and walking as soon as possible. Many worry about waking up with a ventilator tube stuck in their throat — I sure was. But I was so sedated that I barely remember it. They removed mine within a few hours of waking up — that’s not the case for everyone — and transitioned me to an oxygen cannula. I was breathing and walking on my own within 24 hours.

The hospitalization was spent doing tests, learning to breathe and walk again, and learning my new medications and restrictions. After 14 days, I was out of the hospital! I lived within 30 minutes of the hospital for the next six weeks and focused on recovering my stamina.

Check back next week Tuesday to hear about the best part of the transplant process: The rest of my life.

***

Note: Cystic Fibrosis News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Cystic Fibrosis News Today, or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to cystic fibrosis.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.