Ibuprofen Counters Key Bacteria in Lungs of CF Patients, Study Shows

Written by |

Ibuprofen does a good job of fighting bacteria in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients’ lungs, including two key threats, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia, a study shows.

Researchers said the findings support ibuprofen’s use as an add-on therapy against bacterial infections in CF.

The study, “Antimicrobial Activity of Ibuprofen against Cystic Fibrosis-Associated Gram-Negative Pathogens,” was published in the journal Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy.

Clinical trials have shown that adults with CF who receive a high dose of ibuprofen (50 to 100 μg/mL plasma concentration) have less lung function decline and good to excellent pulmonary function.

In children with CF aged 6 to 18 years, high-dose ibuprofen decreased the annual rate of decline in a lung function measurement, compared with placebo-treated children. The measurement was forced vital capacity.

Ibuprofen’s beneficial effects in CF have been linked to its anti-inflammatory properties. But few studies have shown that it also has antimicrobial activity, and none has assessed its potential against bacteria commonly found in the lungs of CF patients.

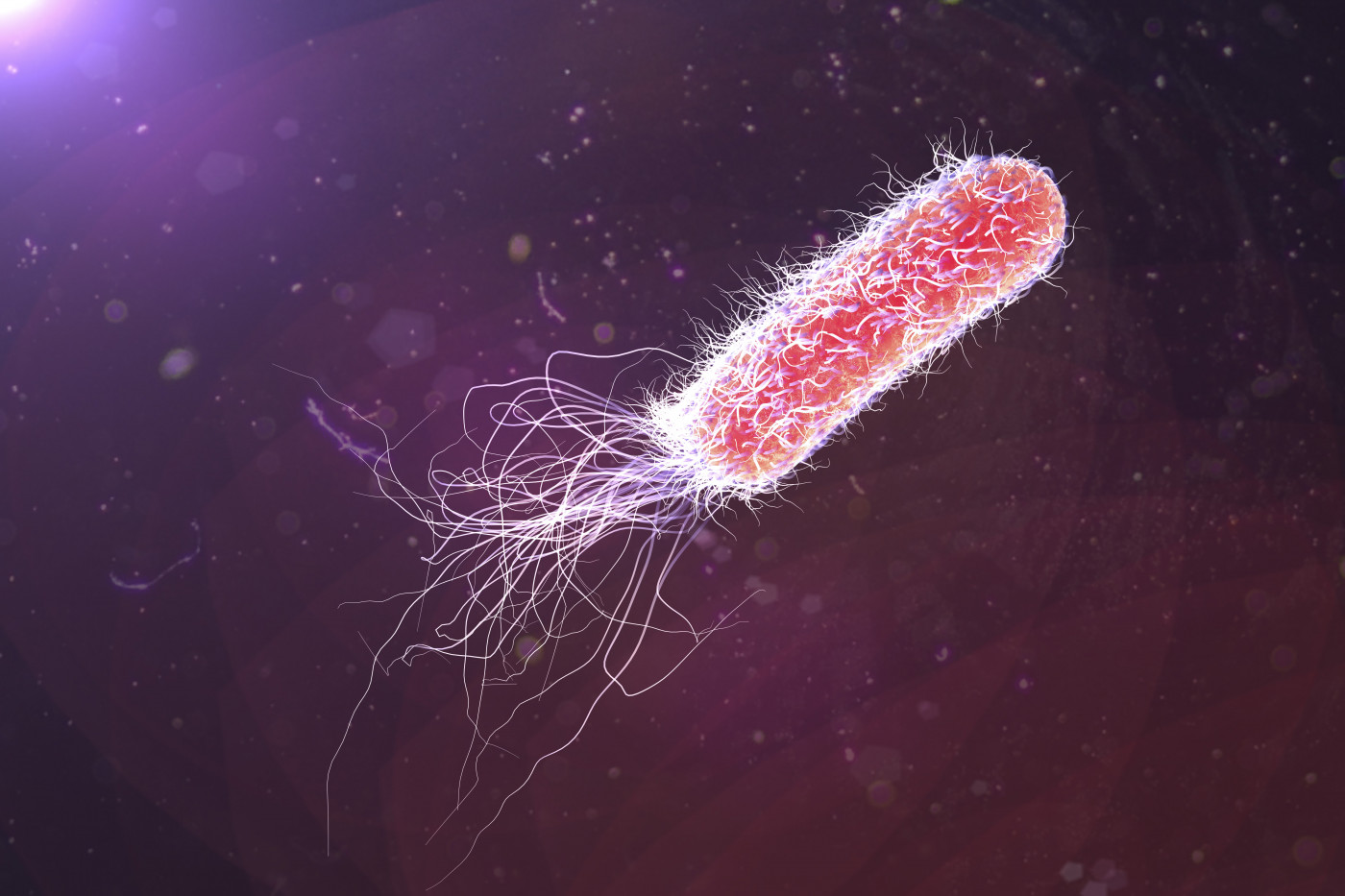

Researchers decided to see whether high doses of ibuprofen could counter Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Burkholderia in their lungs. They used several strains of the two bacteria.

The key finding was a dose-dependent decrease in bacteria after 12 hours of ibuprofen.

For fast-growing bacteria, however, ibuprofen’s clout started to disappear after 12 hours. A new dose extended its antimicrobial effect another 18 hours.

“The initial growth suppression was more robust for the two Burkholderia species strains than for the two P. aeruginosa strains, yet at 18 hours the results were more striking in the case of P. aeruginosa,” the researchers wrote.

The team looked at whether ibuprofen could prevent P. aeruginosa from forming biofilms — clumps of bacteria that are frequently embedded in a self-produced protective matrix.

Ibuprofen delay the bacteria’s ability to form biofilms, the team said.

The researchers also tested ibuprofen’s anti-bacterial effect with a mouse model of acute pneumonia triggered by a P. aeruginosa infection. Oral delivery of ibuprofen, first at two hours after infection and then at eight-hour intervals, significantly decreased bacteria in the lungs and spleen of the animals 36 hours after infection.

In addition, ibuprofen increased the mice’s survival, compared with controls.

“Only one 1 of the 13 mice in the ibuprofen group died of infection over a period of 3 days. In contrast, 6 deaths were recorded among the 14 sham-treated animals [controls] over the same time frame,” the researchers wrote.

The use of oral ibuprofen to treat patients with CF has been limited due to rare cases of kidney toxicity and hemorrhage in the gastrointestinal track.

Because of this, “developing a novel aerosolizable formulation of ibuprofen would be highly advantageous,” the researchers wrote.

The team generated ibuprofen-encapsulated polymeric nanoparticles for aerosol delivery. The new ibuprofen formulation inhibited P. aeruginosa growth in a laboratory setting.

“This approach may be able to provide the target therapeutic dose locally, thereby preserving the beneficial clinical effects while potentially mitigating the toxicity and pharmacokinetic concerns associated with high systemic concentrations resulting from traditional oral therapy,” the researchers wrote.

Overall, the team said the findings showed that ibuprofen has moderate antimicrobial activity that, allied with its robust anti-inflammatory activity, makes it an extremely attractive candidate as an adjunct therapeutic.” They said they hope their findings “will provide an impetus for the adoption of this therapeutic as standard treatment by more CF centers globally.”