25th Anniversary Of Cystic Fibrosis Gene Discovery Breakthrough Commemorated

Written by |

In the 1980’s, life expectancy for persons with CF was just 12 years in the US, and around 20 in Canada. Melissa Benoit spent the first month of her life in the neonatal intensive care unit at The Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids) in Toronto, Canada, where she was diagnosed with a fatal genetic disease called cystic fibrosis (CF). Today, Ms. Benoit is a 31-year-old nurse, wife and new mom; something that may not have been possible without a genetic breakthrough by scientists at the hospital 25 years ago.

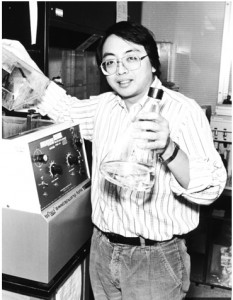

In 1989 a team of researchers at SickKids led by Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui achieved a breakthrough that would not only impact lives of children and young adults with CF, but also pave the way for what is now known as individualized medicine. The scientists discovered the gene that causes cystic fibrosis — CFTR, the first disease-causing gene to be identified, and at the time their discovery, touted as one of the most significant advances in the history of human genetics — is understood to be one of the most significant breakthroughs in human genetics in 50 years, for which Dr. Lap-Chee Tsui was inducted into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame in 2012.

This September, SickKids celebrates the 25th anniversary of the CF gene discovery and progress that has been made both clinically and scientifically.

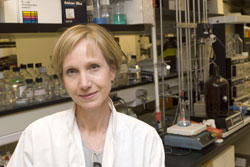

“Finding the gene opened the door to unprecedented knowledge of the disease. After its discovery we were able to study and understand how the protein made by the CFTR gene worked and what happened when it didn’t,” says Dr. Christine Bear Senior Scientist and Co-Director of the CF Centre at SickKids. “Once we figured this out, therapy that targeted defects caused by CF gene mutations could begin.”

Interested in Cystic Fibrosis research? Sign up for our forums and join the conversation!

Dr. Bear says the most controversial question in CF research and treatment currently is that “People are using drastically different approaches to try and develop therapies for CF and it is not always clear which of these approaches is going to end up being the most fruitful. The conversations are sometimes pretty aggressive as people argue amongst themselves which approach is going to be the best. I think that we just need to be able to support a research environment where people are going to be able to develop ideas using multiple approaches at the same time because its hard to predict which approach will lead to discovery.”

“The goal of CF researchers is to create effective therapies for every CF patient. The vision is that the genetic signature of each CF patient will dictate the choice of therapy. This approach will ensure the best clinical response with least number of side effects for each individual,” says Dr. Felix Ratjen, Division Chief of Paediatric Respiratory Medicine at The Hospital for Sick Children, Professor of Paediatrics at The University of Toronto, and Senior Scientist at the Research Institute in the Department of Physiology and Experimental Medicine. “Our team is currently working on patient-specific drug development for the first time in cystic fibrosis research.”

“The goal of CF researchers is to create effective therapies for every CF patient. The vision is that the genetic signature of each CF patient will dictate the choice of therapy. This approach will ensure the best clinical response with least number of side effects for each individual,” says Dr. Felix Ratjen, Division Chief of Paediatric Respiratory Medicine at The Hospital for Sick Children, Professor of Paediatrics at The University of Toronto, and Senior Scientist at the Research Institute in the Department of Physiology and Experimental Medicine. “Our team is currently working on patient-specific drug development for the first time in cystic fibrosis research.”

Dr. Felix Ratjen, who is co-leading the CF centre at SickKids and Medical Director of the Clinical Research Unit, observes that “One of the controversial questions is whether we can use gene therapy to fix CF. There’s been a lot of research into this as a possible solution but there have also been a lot of hurdles. Right now the majority of people would say that it’s not feasible but they may be wrong. So, that’s certainly one of those controversies thats important in CF science right now.”

After the CF gene discovery in 1989, Dr. Tsui set up a mutation database that would house the collection of mutations in the CF gene so researchers around the world could benefit from the most up-to-date genetic information about the disease. This database remains a major resource for clinical and basic research, and serves as a model for other genetic disease databases. In total there are over 1,900 mutations in the CF gene. Scientists have learned that many of these can be classified with respect to the type of defect they cause in the protein. Gaining this understanding has driven the race to find mutation-targeted therapeutics.

After the CF gene discovery in 1989, Dr. Tsui set up a mutation database that would house the collection of mutations in the CF gene so researchers around the world could benefit from the most up-to-date genetic information about the disease. This database remains a major resource for clinical and basic research, and serves as a model for other genetic disease databases. In total there are over 1,900 mutations in the CF gene. Scientists have learned that many of these can be classified with respect to the type of defect they cause in the protein. Gaining this understanding has driven the race to find mutation-targeted therapeutics.

“We are at a new frontier of discovery for CF patients,” Dr. Bear notes in a Hospital For Sick Children release. “Over the past decade there has been tremendous progress with regard to therapy discovery conducted using generic cells induced to possess a particular CF mutant protein. These workhorse cell cultures were then used to identify the types of chemical compounds that can repair the defect caused by that specific mutation. However, there were limitations since these cells did not exactly mimic the cell in the lungs, liver or pancreas of CF patients. While this approach led to the discovery of one drug called KALYDECO, we believe that a new discovery strategy is needed during the upcoming 10 years to find the next generation of therapies effective in treating all CF patients.”

[adrotate group=”1″]

KALYDECO, the drug referred to by Dr. Bear, is exclusively indicated to treat only a relatively small sub-minority of what is an already relatively small number of cystic fibrosis cases overall who have at least one copy of the G551D mutation in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. The CF prevalence rate in general in the most vulnerable ethnic group, Caucasians, is just one in every 2,500 births. Consequently, since the proportion of cystic fibrosis cases positive for the G551D mutation in the CFTR gene is very low and only few CF patients are eligible to use KALYDECO, economies of scale associated with sales of more widely-prescribed drugs don’t apply with KALYDECO, keeping the cost per patient high.

The release notes that the CF story at SickKids has always been one of collaboration. The gene discovery was a partnership between SickKids and the University of Michigan; the creation of the CF mutation database is an international collaboration; and the most recently, the pharmaceutical and philanthropic communities and SickKids came together to develop the first mutation-targeted CF drug, KALYDECO.

“The recent approval of KALYDECO as a drug for some CF patients with specific mutations is evidence that compounds found to repair the primary defect caused by a mutation in the lab, can be translated into drugs that improve the health of CF patients,” says Dr. Bear. “While this is a big step for CF, there is still much work to be done, because this treatment is only effective for a small population of CF patients. We know that a variety of therapies will be needed to make a difference for more CF patients, not only because there are many different CFTR mutations but also because of the uniqueness of each patient. As we speak, we are developing new ways for discover therapies that employ airway cells like those that are affected in CF patients.”

Consequently, the CF Centre at SickKids is focusing its efforts on identifying new lung cell-targeted therapies by testing for compounds that rescue mutant CFTR function. These tests are conducted by robots applying drugs on thousands of tiny wells, with each well each containing cells with a particular CFTR mutation. Scientists can see in real time whether a drug is rescuing mutant CFTR function or not. The top compounds identified in these robotic screens will be tested on cells from individual patients with the goal of finding the best therapy for each individual.

“The key to our continued success has been the partnership with patients and families. Clinicians, scientists and patients are working together to advance treatment and improve outcomes for children and adults living with the disease,” says Dr. Ratjen.

Melissa Benoit has been participating in CF research since she was around nine years old, and some of the experimental therapies she tried as a child are now standard treatment for children born with the disease.

“We wouldn’t be where we are today without ongoing research. In my lifetime alone, the research advances that have been made have had a huge impact on my quality of life and certainly on others living with cystic fibrosis as well,” observes Ms. Benoit. “If my participation in research can help scientists gain a better understanding of the disease and ultimately improve outcomes for those living with cystic fibrosis, then why not?”

Sources:

The Hospital for Sick Children

Vertex Pharmaceuticals

Canadian Medical Hall of Fame

Image Credits

The Hospital for Sick Children

Canadian Medical Hall of Fame