Bioengineer to Use $2M Grant to Study Gene Editing for CF

A bioengineer at Rice University will use a more than $2 million federal grant for a project to “repair” harmful mutations that cause cystic fibrosis (CF) using a potentially more accurate approach to gene editing developed in her lab, the university announced in a press release.

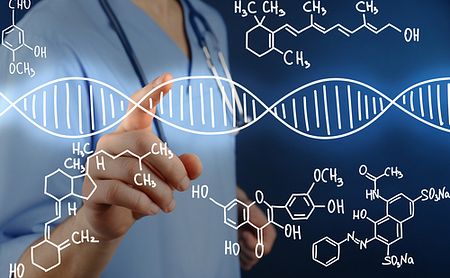

The National Institutes of Health’s four-year award was given to Xue Sherry Gao, PhD, to adapt her lab’s tools to improve the accuracy of CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing in mending CF-causing mutations in the CFTR gene.

This gene is responsible for the CFTR channels that regulate the movement of chloride ions and water through the cell membrane. CFTR malfunctions disrupt this process, resulting in thick mucous accumulating in the lungs and other organs.

Although the number of effective medications for CF is growing, they must be taken for a patient’s life. Correcting the mutation causing CF marks a permanent and potentially curative change.

CRISPR/Cas9 is a gene editing technology derived from the bacterial defense against infection. It essentially forms a pair of shears that can be directed to specific sites along a strand of DNA, such as the CFTR gene.

“The problem is CFTR is a huge gene,” Gao said. “Researchers have checked genetic mutations in this specific gene, and they found there are more than 2,000 variations. Not all of them lead to the disease, but it’s believed more than 350 of the mutations cause cystic fibrosis.”

Altering the mutations while leaving the rest of the gene intact differs from many gene therapy approaches. This therapy, to date, often seeks to replace an entire faulty gene with a healthy version. CFTR‘s size, however, complicates that approach.

“Because the gene is so large, it’s difficult to use gene therapy to deliver a good copy of CFTR and restore the function,” Gao said. “The technology we want to use is called gene editing. Instead of replacing a gene, we are trying to fix it.”

To improve its accuracy and reduce the risk of off-target effects, her approach cuts one side of the double-stranded DNA rather than both.

Gao began developing this gene editing approach while investigating genetic hearing loss. In 2018, she published research in which she and colleagues reduced the hearing loss of the aptly named Beethoven mouse model for genetic deafness.

This research led Gao to cystic fibrosis and CFTR mutations.

One challenge in her new project will be to simultaneously edit multiple mutations in a single patient’s CFTR gene, as each individual CF case may stem from numerous mutations at different locations along the gene.

Gao’s results could aid CF that goes beyond treatment.

“It will also allow us to create a library of cystic fibrosis cell lines we can use to study whether small molecule drugs are effective,” she said. “We want to achieve a more personalized gene therapy for cystic fibrosis as well as for many other genetic diseases.”