Gene-Editing Strategy Successfully Corrects Genetic Error in Human Embryos

Written by |

In a groundbreaking study, scientists reported editing and correcting, for the first time, a defective gene in human embryos. Additionally, this gene-editing technique appeared to be safely performed without introducing additional harmful genetic alterations. These results represent a key achievement in human genetic engineering and highlight a potential way forward for addressing diseases with a genetic cause, such as cystic fibrosis.

The study, “Correction of a pathogenic gene mutation in human embryos,” was published in the journal Nature.

Mutations (errors) in a single gene have been identified as the underlying cause of more than 10,000 inherited disorders, affecting millions of people worldwide. One of these mutations affects the MYBPC3 gene, causing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). This inherited disorder is characterized by an enlarged (hypertrophic) section of the myocardium, the heart’s muscle, making it more difficult for the heart to pump blood out to the rest of the body.

“Recent developments in precise genome-editing techniques and their successful applications in animal models have provided an option for correcting human germline mutations,” the study’s authors wrote. Germline mutations occur in the germ cells (eggs or sperm) and are transmitted to the offspring.

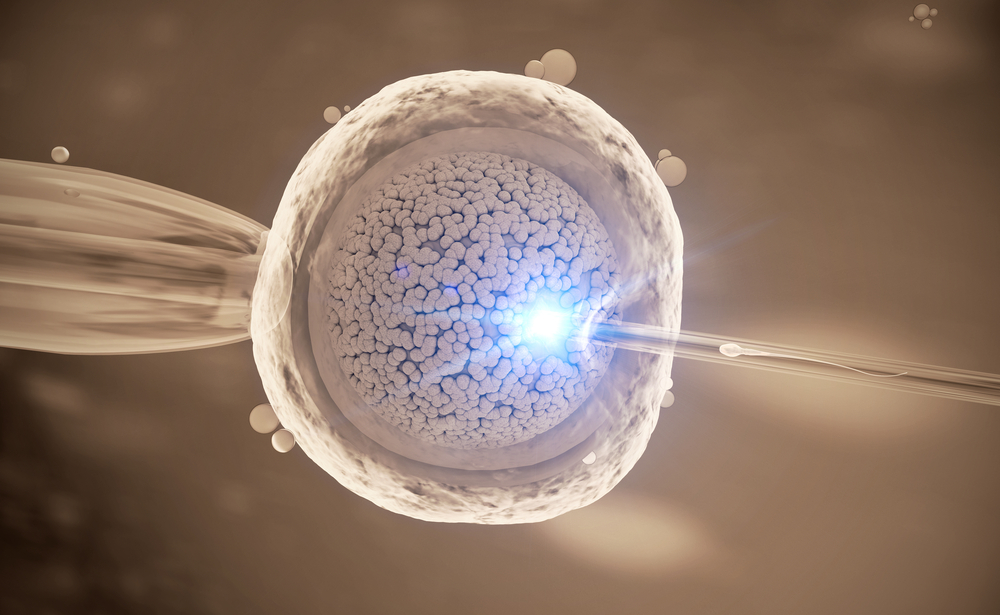

A strategy to prevent the transmission of the mutation to the offspring is preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), where embryos are genetically investigated for mutations. Those that are mutation-free can then proceed to implantation in the context of in vitro fertilization (IVF).

“When only one parent carries a heterozygous mutation, 50% of the embryos should be mutation-free and available for transfer, while the remaining carrier embryos are discarded. Gene correction would rescue mutant embryos, increase the number of embryos available for transfer and ultimately improve pregnancy rates,” researchers explained.

Scientists used the genome-editing technique called CRISPR–Cas9 to establish whether they could correct the mutation on the MYBPC3 gene in human preimplantation embryos carrying the defect. As with many diseases caused by genetic defects, therapeutics currently available only improve a disease’s symptoms without addressing its genetic cause.

Remarkably, this study’s strategy was successfully applied, and scientists were able to correct the defect in two-thirds of embryos. None of the embryos appeared to carry any additional, harmful mutation.

“The efficiency, accuracy and safety of the approach presented suggest that it has potential to be used for the correction of heritable mutations in human embryos by complementing preimplantation genetic diagnosis. However, much remains to be considered before clinical applications, including the reproducibility of the technique with other heterozygous mutations,” the study concluded.