Work in Progress on Challenges of Minority Representation in CF Trials

Written by |

ESB Professional/Shutterstock)

Proper representation in clinical trials has long been a challenge for minorities with rare diseases like cystic fibrosis (CF), risking — and often leading to — inequities in care and fewer effective treatments for these patients.

To this end, members of the CF community, including patients, researchers, physicians, and nonprofits, are working toward building more trust among minority communities to improve their participation in clinical trials, with the hope of developing more inclusive treatments.

On the flip side, there is a need for more knowledge and awareness among healthcare providers and the research community on the prevalence of CF among minority populations to improve accuracy and time to diagnosis, boost minority enrollment in trials, and design more effective treatments for them.

Michele and Terry Wright embrace as she receives the 2019 Vision Voice Award at the 4th Annual Equanimity Awards Red Carpet Gala in Grapevine, Texas. (Photos courtesy of Michele Wright)

Part of the issue stems from the once-pervasive idea that CF affects only whites. And while the disease is more common in Caucasians, it is now known to occur in minorities at a rate higher than previously thought. Still, Black people, Hispanics, and other racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to experience a delay in diagnosis. They also are more likely than white people to have rare CF mutations that may not be detected on prenatal or newborn screening tests.

Terry Wright, 58, founder of the National Organization of African Americans with Cystic Fibrosis (NOAACF), had classic disease symptoms — severe gastrointestinal pain, mucus buildup in the lungs, and salty sweat — but no diagnosis for five decades.

His wife, Michele, 55, a co-founder of the organization, recalled seeing a doctor in 2000 who took a CF diagnosis off the table.

“That physician said, ‘If you were not African American, I would say you had cystic fibrosis,'” Michele Wright, who lives in Little Rock, Arkansas, said in a phone interview with Cystic Fibrosis News Today. “That was the first time and the last time he had heard of it until he was diagnosed.”

That diagnosis didn’t come until 2017, when Terry Wright was 54 years old.

While the exact incidence of CF in Black people isn’t entirely known due to underreporting, the NOAACF estimates it at 1 in every 17,000 births. And the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation’s (CFF) Patient Registry found that between 1999 and 2014, the percentage of minorities with CF rose from 5% to 8.2% for Latinos, from 3% to 4.6% for Black people, and from 1.4% to 3.1% for other races.

Even with the reported number of minorities with CF increasing, racially representative clinical trials are lacking, and treatments like CFTR modulators aren’t reaching minorities because of their higher share of rare mutations.

Treatments and rare mutations

According to a 2016 study published in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society, only 19.7% of the selected 147 pharmacology clinical trials reported information on patients by race or ethnicity. Latinos were verified as included in 7.5% of those clinical trials, Black patients in 6.8%, and Asians in 2%. For the 29 clinical trials that did report race, the percentage minority makeup was 2% for Latinos, 1% for Black people, and 0.1% for Asians.

When clinical trials use inclusion criteria that prevents a swath of minorities with a rare mutation from enrolling in a study, it’s difficult to determine if the treatment will be as effective for them. According to the CFF, minorities make up 40% of the people who aren’t candidates for CFTR modulators due to their specific mutation.

“You think that you would want to develop drugs, and include the patients who are the sickest and suffering the most,” Meghan McGarry, one of the two authors of that 2016 study and a pediatric pulmonologist at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, said in a phone interview with CF News Today. “And these are the people who are not being included in studies.”

Because of a lack of that representation, McGarry said, treatments coming out of the pipeline are not as effective for minorities. Another recent study she co-authored found that 92.4% of white patients qualify for approved CFTR modulators, while the percentage of minorities eligible for these therapies are lower — 75.6% of Latinos, and 69.7% of Black patients, and 80.5% of those of other races.

A triple-combination therapy, Trikafta (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor) was initially approved in October 2019 for certain mutations mainly found in white CF patients. In December 2020, its U.S. approval was expanded to include more than 600 additional patients with rare CFTR mutations, including Wright’s.

Since Wright added Trikafta to his regimen, which also includes AffloVest percussive therapy, antifungals, antibiotics, and medicinal herbs he grows himself, he says he’s had less pain in his gastrointestinal tract and clearer sinuses.

Still, Trikafta is available for only about 180 CFTR mutations of an estimated 1,700 — nearly 1,000 of which are specific to just one or two people. JP Clancy, vice president of clinical research at that CFF, said that gene therapy, while still primarily in the preclinical research phase, is a type of “mutation-agnostic” solution that might restore CFTR gene function in all patients.

Rebuilding trust

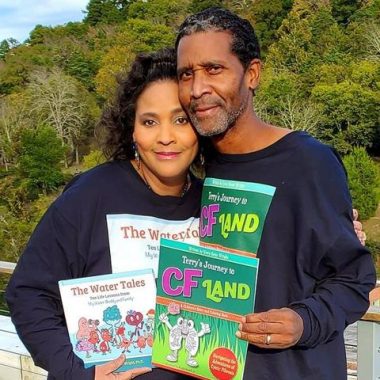

The Wrights celebrated 20 years of marriage and the release of books they wrote for children on Nov. 4, 2020.

The Wrights started an initiative, Advocating for Health Equity and Addressing Disparities (AHEAD), aimed at increasing awareness of health disparities in minority communities and educating organizations, businesses, and corporations on the issue.

“If the people at the table, your thought leaders, your decision-makers, don’t reflect that work equity, then you can forget health equity and clinical trial equity,” said Michele Wright, a former pharmaceutical company executive.

Clancy said the CFF is still primarily in the listening phase in regard to health equity and a lack of minority trial representation. However, it’s started survey work in its research coordinator network, which includes the people primarily interacting with patients, and developed a deeper cultural competency toolkit for that group. He expects that the process of addressing these issues might take some time, but not for lack of trying.

“If you want to get meaningful data and have meaningful conversations with BIPOC [Black, Indigenous, and people of color] communities, it takes time to build that trust. It doesn’t come overnight,” Clancy said. “And it comes through authentic communications that really demonstrate our commitment.”

Hiring diverse staff may be one way to build trust among minority communities. Interacting with clinicians, doctors, and translators that reflect a patient’s race could help overcome feelings of mistrust because of the mistreatment of Black people in the past, specifically as a result of the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, and language or culture barriers for various minority groups.

Michele Wright, who was born in the hospital in which the Tuskegee experiment occurred, emphasized collective action is needed by biotech companies and the larger CF organizations, such as supporting underrepresented groups and “putting money where their mouth is,” she said.

“This is something that’s going to take a collective community effort to address. It’s not passing out paper and hoping people sign up,” Michele Wright added. “It’s going to take a strategic collective cohesive plan to overcome.”