Couple’s Goal: Health Equity for Black and Minority CF Community

Written by |

Photo courtesy of Michele Wright

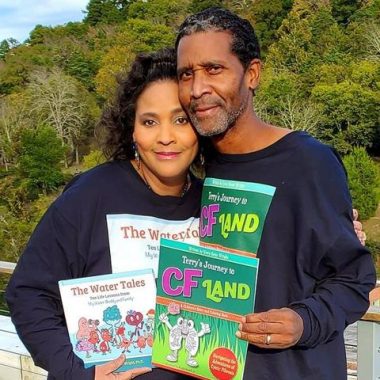

Michele and Terry Wright, founders of NOAACF.

Diagnostic odysseys are common for people with rare diseases. But for Terry Wright, it took 54 years of gastrointestinal pain, lungs clogged with mucus, countless emergency room trips to treat pneumonia, and surgeries to get to the bottom of a disease that should have been clear from the beginning: cystic fibrosis (CF).

Wright, now 58, and his wife, Michele, attribute his decades-long delay to a medical community that has long viewed CF as a white person’s disease and hesitated to diagnose him, preventing him from getting the treatments needed to manage the condition. A doctor the couple saw 20 years ago discounted Wright’s symptoms as indicative of CF simply because he was African American.

Michele and Terry Wright, ready for separate health checkups. (Photos courtesy of Michele Wright)

“That was the first and last time he heard of [CF] until he was diagnosed,” Michele Wright said.

Wright’s experience led him and his wife to become advocates for greater health equity for Black people with CF and to raise awareness about the disease within the Black community.

They founded the National Organization of African Americans with Cystic Fibrosis (NOAACF), where Wright now serves as president and Michele Wright as the executive director. Through the nonprofit, they have developed diagnostic tools for minority communities, organized conferences centered around health equity — the idea that everyone should have the same level of healthcare regardless of race or economic background — and have spoken and written about the stereotype that CF only affects white people.

Proper genetic testing at birth and an understanding that CF does, in fact, affect Black people could have allowed Terry Wright to access treatments to better manage his symptoms starting in childhood.

Journey to diagnosis

Wright, born and raised in Little Rock, Arkansas, was 4 years old when the extreme abdominal pain started, often missing school because of it. Doctors diagnosed him with stomach ulcers, sending him home with pain medications and a lack of answers.

“There were many days wishing I was just dead,” said Wright in an interview with Cystic Fibrosis News Today from his home in nearby North Little Rock. “I was always trying to put myself in a comfortable position that if I could hold for at least two minutes, I would be all right.”

He also had continuous problems with his sinuses and coughing up of mucus, and said he was constantly being hospitalized with pneumonia. Asthma was the culprit this time, according to his doctors.

He went on to become a personal trainer, running marathons, biking 100 miles, and stretching his body to the limit, all the while noticing that salt clung to his body after sweating. He sometimes became so dehydrated, he would faint.

It wasn’t until 2000, at the age of 38, that Wright even heard of CF, despite his showing all the classic signs of the disease. But because of Wright’s race, the doctor who mentioned it didn’t pursue work that could have diagnosed his CF.

He finally discovered he had the disease 17 years later, at the age of 54. Doctors at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences ordered the tests that identified the genetic mutation behind his symptoms.

Now, Wright is treating his CF with Trikafta (elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor), a triple-combination CFTR modulator developed by Vertex Pharmaceuticals. He was among the 600 patients who gained access to the therapy when its approval was expanded in December 2020 to cover more rare mutations.

Addressing health inequity

The Wrights reported using at least $35,000 of their own money to support NOAACF programs and independent health education projects this year. They hope to bring in another $100,000 to $250,000 to grow their own organization and to help other foundations also working to improve health access for Latinos, Native Americans, and Blacks in the U.S.

Early diagnosis is a focus for the couple because, while newborns are commonly screened for CF (it is included on the recommended uniform screening panel), some of the rarer mutations often found in minority groups can be missed. If the mutation doesn’t show up on a screening, doctors typically won’t order the sweat chloride test that would confirm a CF diagnosis.

Delays in diagnosis or misdiagnoses mean delays in proper treatment and care, which can lead to worse health outcomes.

To assist with early and accurate diagnoses, NOAACF will soon launch a checklist, called the Wright Cystic Fibrosis Screening Tool, in both paper and online versions. Use of the tool is twofold: It can help people self-identify symptoms that could be related to CF, and it can assist healthcare providers in identifying people who may have the disease, especially those in minority groups, where CF is often overlooked. The couple plan on promoting it to healthcare professionals, as well as to CF patients, caregivers, and families, through third-party partnerships and direct sales marketing.

The Wrights celebrated 20 years of marriage and the release of their two children’s books on Nov. 4, 2020.

The Wrights also recently launched a NOAACF initiative called Advocating for Health Equity and Addressing Disparities (AHEAD). The idea of the program, which is still in planning stages, is to train healthcare providers so they can improve health equity in their facilities.

AHEAD is to open with the couple evaluating a potential client’s culture with regard to healthcare and race, finding areas of improvement. Next, they move into action, educating employees and creating a plan for better health outcomes among minorities.

In February, NOAACF hosted its first virtual conference, titled “Blacks, Indigenous, and Other Minority Ethnicities with Rare and Genetic Diseases,” aimed at raising awareness of rare conditions in those communities. CF and lupus were focuses of the two-hour meeting.

“Our goal is to be the voice of African Americans with cystic fibrosis and to be a bridge of hope for all individuals with cystic fibrosis and the BIPOC [Black, indigenous, and people of color] community,” Michele Wright said.

Terry Wright also published a children’s book, “Terry’s Journey to CF Land: Navigating the Adventures of Cystic Fibrosis,” which tells his story of dealing with CF without a diagnosis in a fantastical, age-appropriate format.

“He wrote and released this to help inspire, uplift, and amuse children who have cystic fibrosis and empower them on their own journey to CF land,” Michele Wright said about the book, which has been available on Amazon since January.

NOAACF also branched out to the film world, releasing a short dramatization of Terry’s story, “54 Years Late,” written and directed by Michele Wright. She started drafting the script in April when she found out about the CF Awareness Film Festival deadline in May and, within a week, had filmed, edited, and produced it.

It won the best documentary award at the festival, and has received a handful of other awards. Once the movie has finished screenings at film festivals, it is to be released nationally, and the Wrights are hoping to later turn it into a full-length feature film.

Beyond his advocacy work with the NOAACF, Wright continues his job as a personal trainer. He also has a love for the outdoors and horticulture, tending to his late grandmother’s land, planting more than 150 trees, plants, and herbs. Gardening has reduced his CF-induced anxiety, he said, and the herbs he grows — like turmeric, elecampane, and peppermint — have helped him manage his symptoms. In 2010, he became an Arkansas certified master gardener, interviewing and studying for the position from his hospital bed where he was recovering from double pneumonia, sinusitis, and bronchitis.

Terry Wright’s hope is that no one will have to suffer with CF or other disorders for as long as he did without an answer because of their skin color.

“People were still shocked seeing a Black male in the hospital with cystic fibrosis,” Michele Wright said. “It’s gonna be good when we get to the day that’s no longer a surprise.”