Research May Explain Why Different CF Bacteria Infect at Certain Ages

Written by |

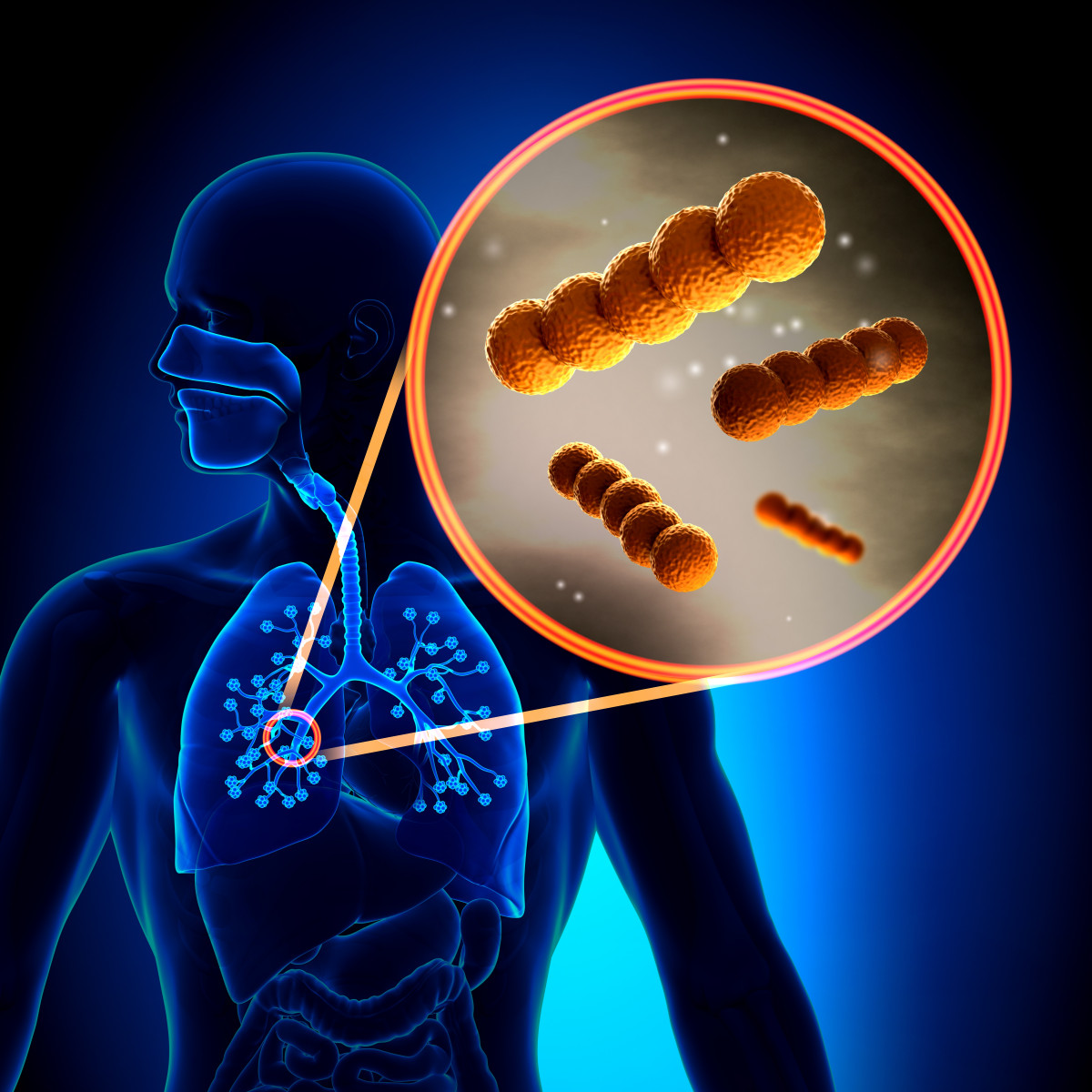

New research unveils why the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa cause sustained infections in younger cystic fibrosis (CF) patients, while the bacteria Burkholderia cepacia complex infects patients as teenagers and adults.

The findings show that P. aeruginosa loses the ability to use its toxic weaponry after it adapts to the lungs, allowing Burkholderia cepacia complex to establish an infection.

The study “Host Adaptation Predisposes Pseudomonas aeruginosa to Type VI Secretion System-Mediated Predation by the Burkholderia cepaciaComplex” was published in the journal Cell Host & Microbe.

Burkholderia cepacia complex and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are two strains of opportunistic bacteria that often cause respiratory infections in people with CF.

However, these bacteria infect patients differently according to their age: P. aeruginosa typically infect infants or young children, whereas Burkholderia cepacia complex infects teenagers and adults. P. aeruginosa infection also persists for life, while infection with Burkholderia is rare, but can be deadly if established.

Reasons for this apparent age discrimination were unknown.

A team led by researchers at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, School of Medicine showed that bacteria deploy an ‘arsenal’ — called Type VI Secretion Systems (T6SS) — to kill their competitors.

Researchers isolated P. aeruginosa from infants and young children, and Andrew Perault, PhD (the study’s first author) conducted “competition” experiments between both bacteria strains. They found that Pseudomonas bacteria use their T6SS — a complex of proteins that sit at the bacteria’s membrane and “shoots” toxins that aid in infection — to kill competitor bacteria, including Burkholderia.

“This may be one of the reasons Burkholderia does not take root in young patients,” Peggy Cotter, PhD, a professor in the UNC Department of Microbiology and Immunology and the study’s lead author, said in a UNC press release.

“Andy [Andrew Perault] showed that although Burkholderia also produce T6SSs, they cannot effectively compete with Pseudomonas isolates taken from young CF patients,” Cotter said.

A key difference between these strains is the ability of P. aeruginosa to adapt to the lung of young CF patients and sustain a long-term infection. But as P. aeruginosa adapts, it loses its ability to produce the ‘shooting’ complex, T6SS, and consequently the ability to fight Burkholderia.

At this stage, and typically among older patients, Burkholderia takes the lead and is able to kill Pseudomonas to establish its infection.

“We believe the findings of our study, at least in part, may explain why Burkholderia infections are limited to older CF patients,” Perault said. “It appears that as at least some strains of Pseudomonas evolve to persist in the CF lung, they also evolve to lose their T6SSs, and hence their competitive edge over Burkholderia, which are then free to colonize the respiratory tract.”

These “findings suggest certain mutations that arise as P. aeruginosa adapts to the CF lung abrogate T6SS activity, making P. aeruginosa and its human host susceptible to potentially fatal [Burkholderia] superinfection,” the researchers wrote.

According to the team, targeting and blocking the T6SS of Burkholderia could potentially help prevent the bacteria from establishing an infection, while assessing the effectiveness of P. aeruginosa T6SS in a CF patient’s lungs may help to identify those more at risk for Burkholderia infections.