Resistance Training Favorably Affects Youngsters’ Heart Rate

Written by |

A clinical study found that in youth with cystic fibrosis (CF) who are in good physical condition, resistance training favorably regulates heart rate variability (HRV), an indicator of the ability to adjust to stress.

HRV, a measure of the variation in time between each heartbeat, is an assessment of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates involuntary body functions like heart rate, digestion, and breathing.

“Our findings support the effectiveness of a short-term exercise resistance training program to modulate HRV in children and adolescents with CF presenting mild to moderate lung function impairment and a good physical state,” the investigators wrote.

The study, “Effects of a Short-Term Resistance-Training Program on Heart Rate Variability in Children With Cystic Fibrosis—A Randomized Controlled Trial,” was published in the journal Frontiers in Physiology.

CF results from a defect in the CFTR protein, which is known to negatively affect the function of the lungs. However, its effects on the autonomic nervous system remain less understood.

In healthy adults and children, exercise can improve autonomic regulation of the heart by modulating HRV. Children with CF experience exercise intolerance (decreased ability to perform physical exercise) and higher perceived fatigue, which contribute to sedentary habits that may hinder prognosis of the disease. Working CFTR deficiency in the muscle has been associated with exercise intolerance and decreased muscle strength, a comnbination that can impair autonomic response.

A clinical trial (NCT04293926) was conducted in Spain to evaluate the effects of a short-term resistance exercise program on HRV in children and adolescents with CF.

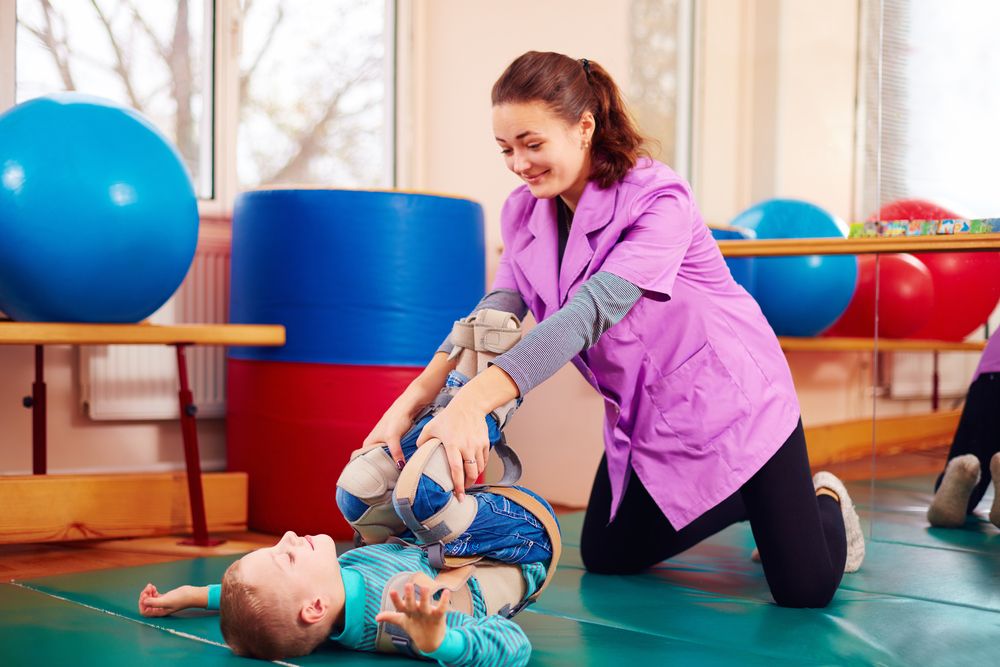

A total of 19 participants were included in the study and assigned randomly to an exercise group or a control group. The exercise group participated in three hour-long resistance training sessions per week for eight weeks. Each session consisted of a warm-up period of 15 minutes, resistance exercises of both upper and lower limbs for 35 minutes, and a cool-down lasting 10 minutes. The protocol was divided into a first phase focusing on technique and execution, and a second phase on strength. Patients in the control group followed the common recommendations of the CF multidisciplinary team, including proper nutrition and physical activity.

Most participants (13, or 68.4%) were male. Ages ranged from 7 to 19, with a mean age of 12.2.

At study start, the participants had mild-to-moderate lung function impairments, measured by parameters such as the amount of air they could expel from their lungs in one second, and their peak oxygen intake.

Compared with the control group, the exercise group showed a significant increase in mean muscle strength (seated bench press, chest, and back) and a more favorable heart rate recovery measured two minutes after completing the exercise.

HRV is assessed by measuring electrical activity, including a low-frequency component often used as an assessment of sympathetic activity (sometimes called “fight-or-flight”) and a high-frequency component that corresponds with the parasympathetic response (“rest-and-digest”).

A higher HRV has been linked to an improved ability to adjust to stress. The low-to-high frequency ratio has been proposed as an indicator of the balance of sympathetic to parasympathetic regulation of the autonomic nervous system.

Compared to the control group, the exercise group had a significant decrease in the low-frequency reading and the low-to-high frequency ratio, and a significant increase in the high-frequency reading.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the influence of an exercise program on HVR in children and adolescents with CF,” the researchers wrote. “The use of long-term HRV protocols could improve the precision of data collection,” they added.

The study was limited by its small size and exclusion of children and adolescents with CF who were not physically fit, the team noted.