UNC School of Medicine Researchers Find Increased Mucin Levels in Cystic Fibrosis Secretions

Written by |

A group of thirteen scientists at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine may know why certain cystic fibrosis treatments improve lung function. Their answer: mucins, the proteins within mucus. “Our finding suggests that diluting the concentration of mucins in cystic fibrosis mucus is a key to better treatments,” said Mehmet Kesimer, PhD, co-senior author of the group’s paper published in Journal of Clinical Investigations.

A group of thirteen scientists at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine may know why certain cystic fibrosis treatments improve lung function. Their answer: mucins, the proteins within mucus. “Our finding suggests that diluting the concentration of mucins in cystic fibrosis mucus is a key to better treatments,” said Mehmet Kesimer, PhD, co-senior author of the group’s paper published in Journal of Clinical Investigations.

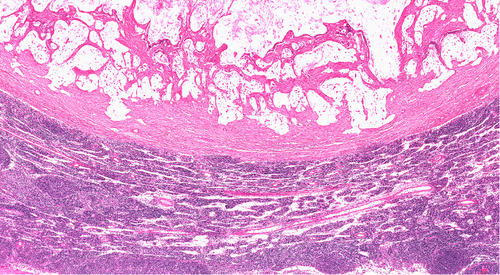

When Dr. Kesimer, along with lead author Ashley Henderson, MD, and Richard Boucher, MD, looked at mucin levels in cystic fibrosis sputum and compared them to levels from normal sputum. Their physical size exclusion chromatography/differential refractometry technique identified three-times higher levels in cystic fibrosis sections. The water-draining power of the cystic fibrosis mucus layer was also increased, which in turn hindered mucus clearance from the lungs. “We think this study shows why nebulized hypertonic saline [sterile salty water] improves the hydration of the cystic fibrosis airway, improves the patient’s mucus clearance and, in so doing, increases lung function,” said Dr. Henderson in a news release from the school.

It has long been known mucus clearance failure in cystic fibrosis patients leads to chronic lung infections and inflammation. The defective CFTR gene of cystic fibrosis patients prevents the normal clearance of mucus present in the lungs to trap contaminants found in the air. “The vast majority of mucus is water, but 30 to 35% of the remaining solid material is made up of mucins,” said Dr. Kesimer. “They form a network of bonds that serves as a framework.” This might be why cystic fibrosis mucus is typically drier than normal mucus: there is more protein than usual, making mucus even more gel-like.

Another highlight of the study was a dispute of another study conducted in 2004 by a different groups that identified decreased levels of mucins in cystic fibrosis sputum. The difference in conclusions was a result of the techniques employed. Whereas the present study used chromatography to isolate mucins and measure their concentration, the 2004 study used western blots. Artifacts were introduced into the western blot method because mucus contains proteases that destroy antibody recognition sites on mucins. “For that reason, we saw less antibody response using the western blot,” said Dr. Kesimer, indicating their group found similar results when replicating the experiment. “But by using more accurate methods, we clearly saw the increase of mucins. In fact, we’ve analyzed many samples of sputum from patients with other chronic pulmonary diseases and we saw the increase in mucins in them, as well.”

[adrotate group=”1″]

The study also found a six-fold increase in osmotic pressure, which complements earlier studies that show increased pressure crushes the ciliated epithelial cells of the lungs that brush away mucus.

“This paper points to a therapeutic strategy to rectify this problem of mucus clearance and provides signposts, or biomarkers, to guide development of novel therapies,” concluded Dr. Boucher.