Researchers Working on Vaccine Against P. aeruginosa Before Infection Sets In

Written by |

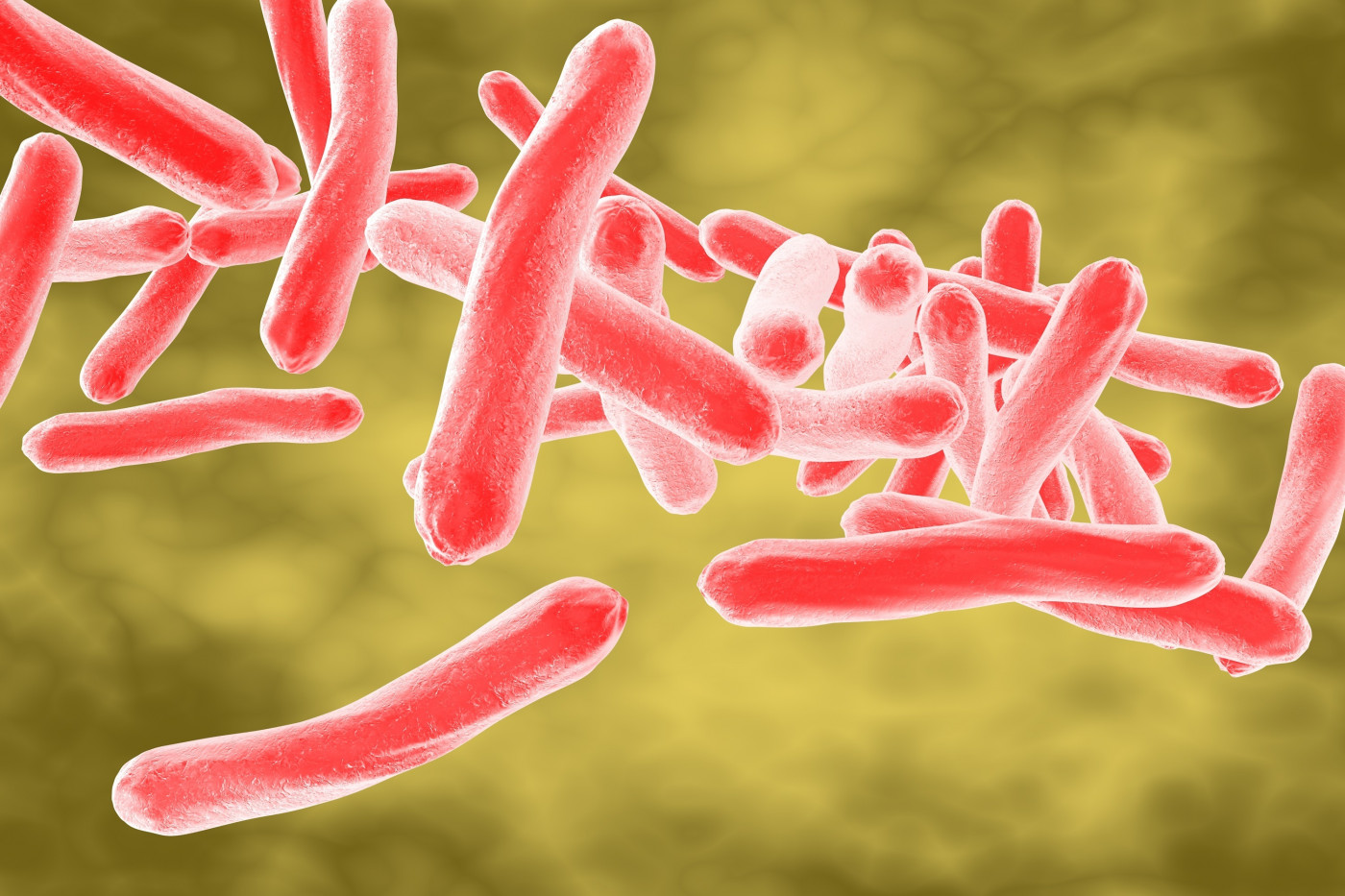

Researchers at West Virginia University (WVU) are working to develop a vaccine against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the highly treatment-resistant bacteria that are a frequent cause of chronic lung infection and damage in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients.

P. aeruginosa is considered a serious health threat by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) because of its ability to survive a range of antibiotics, and — even if reduced to low numbers — to return and do damage.

“Pseudomonas has acquired throughout its evolution numerous intrinsic mechanisms of resistance, making it naturally resistant to a large number of antibiotics. And that’s just the baseline,” Mariette Barbier, PhD, assistant professor in WVU’s School of Medicine, said in a press release.

Increasingly, research is focused on developing a vaccine to prevent bacterial colonization, and subsequent lung damage, in CF and other patients. Infections linked to its presence are a cause of serious pneumonia.

“Dr. Barbier has identified an Achilles’ heel of the pathogen, which can be used to educate the immune system to clear the organism,” said Heath Damron, PhD, director of the Vaccine Development Center at WVU.

Barbier and colleagues published a study in 2016, detailing work to screen the bacteria’s total messenger RNA, also called its transcriptome — the collection of genetic material that lead to the production of proteins — at early stages of an infection in a mouse model. They also analyzed the transcriptome of mice.

“If you sequence the genome, you get everything single thing that it could do,” Barbier said, “but if you sequence the RNA, you get an idea of what the cells are doing right now.”

Researchers found that, during an infection, both bacteria and the host battled for iron acquisition, with each activating iron sequestering pathways.

“It was known for a really long time that iron was essential for humans and bacteria, but seeing it in that way — that interplay of all those proteins just trying to get ahold of it in the model — was unique,” Barbier said.

They designed a large molecule that includes several fragments of the bacteria’s iron-acquisition proteins, and used the molecule to immunize mice and induce an immune response against the bacteria — before the animals became infected, the principle behind a vaccine.

Researchers showed that once these animals were infected with P. aeruginosa, their immune system effectively killed 99.9 percent of the bacteria.

“I think that this 99.9 percent is great,” said Barbier, “but there still are a lot of bacteria in there. We hope to even further improve that efficacy.”

Barbier and her team are now investigating which immune cells are responsible for protecting against P. aeruginosa. Identifying the molecular cascade that encompasses the immune system’s initial detection of the bacteria through to its killing will help the researchers fine-tune their vaccine.

They are also exploring multi-target vaccines, those generated from multiple bacterial proteins.

“Pseudomonas adapts,” Barbier said, “so, if you hit it with one thing … it’s going to be annoyed for a little bit, and then it’s going to say, ‘You know what? I’ll find another way.’ We want to make a multivalent vaccine to provide a broader protection—something that bacteria cannot evolve around.”

A possible strategy, increasingly used in cancer immunotherapies, is via adjuvants — different agents in a vaccine to boost the immune system’s response. Another strategy is testing different ways to deliver the vaccine, either by injections or sprayed into the nasal cavities, to determine the most effective approach.

Barbier suggested that an inhaled vaccine might be most effective against these bacteria in people with respiratory infections.

Her work is being supported by separate grants awarded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation, by the National Institutes of Health, and the West Virginia Higher Education Policy Commission.