Children Teach Us How to Love People with Health Conditions and Disabilities

Written by |

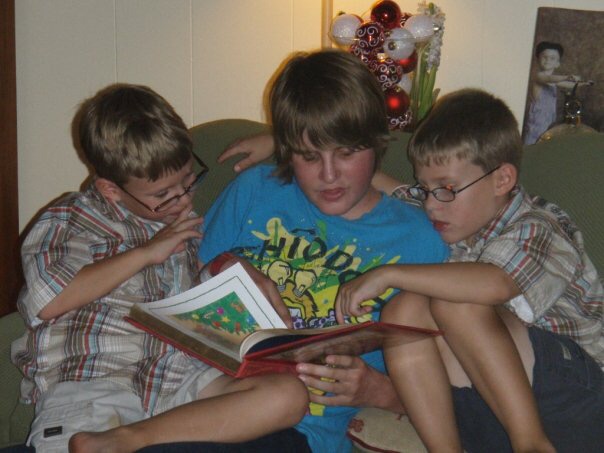

(Photo by Kathleen Sheffer)

A running joke among my friends is that “Brad hates kids.” Maybe I did. I could blame that on my obsession with having adult friends as a teen — in comparison to them, children seemed so naive. So yeah, people would always find me rolling my eyes at kids or saying their jokes are stupid. The classic warning? “Oh, don’t leave your kid around Brad because he’ll hurt their feelings.”

Good warning, honestly.

But something shifted. Near what should have been the end of my life, I found myself wanting to be surrounded by those near their beginning. While awaiting double-lung transplantation and recovering from it, I realized that “naive” children are chock full of wisdom that most adults mysteriously and tragically lose. This wisdom extends to how to treat people with disabilities and chronic illness.

Join the Cystic Fibrosis News Today forums: an online community especially for patients with CF.

Adults are awkward, children are curious

Around me, many adults act like they’re treading barefoot through a sea of Lego bricks. They think one wrong phrase or look will trigger me, melting me into a pond of extra salty CF tears. Upon meeting me, they query preferred terminology, veins burst from their foreheads as they wrestle the temptation to glance at my oxygen tanks, and they constantly ask what I need help with — and then second-guess if it’s rude to ask that. They don’t realize that in their intense efforts to treat me as human-first rather than disease-first, they are constantly reminding me that I have a disease and that they think I’m fragile because of it.

Meanwhile, kids just walk up, ask questions (while parents try to hush them), and then move on. They run up to the elephant in the room and hug it. One kid at church skipped up and asked, “What are the gas tanks for?” I explained my supplemental oxygen (“Helps me breathe, lil dude!”), and he asked how they work. Then, he nodded, stood on tippy-toes, and squeezed my cheeks while giggling at my annoyed expressions. His curiosity quenched, he had turned his attention from my disease to … me.

Children don’t view diseases as shameful

Once in a hospital elevator with my mask on, a little boy stared at me in wonder. Suddenly, his mom yanked him back, pointed at me, and warned loudly, “Watch out, stay away. He’s one of the bad ones.” The kid’s expression collapsed into confusion. The mom taught the boy to treat people with illness as bad people. That sucks.

On the other hand, if I meet a kid while my mask is on and they talk before their parents do, they’ll say I look like Darth Vader, a ninja, or a superhero. They gaze in amazement — he’s cool! They make me feel confident. Once, a boy in a Greek restaurant pointed at my cochlear implants and asked loudly, “What are thooose?!” His horrified dad shushed him and mouthed an apology. I grinned, then set my gyro down to explain the implants. The dad still looked awkward, but the boy whispered loudly, “That’s sooo cool! Like Star Wars!” I laughed and said, “Yeah, like Star Wars!” My implants usually embarrass me, but this kid made me feel kinda dope — that confidence lasted days.

One of my treasured recurring moments is when a kid in a dining area or in front of me in a line can’t stop staring at my mask, and I wink at them, joy in my eyes. Their thrill at being recognized by the “superhero” stretches their smiles wide, wide, wide.

They’re faithful

In Christian circles, we use the term “childlike faith.” Children believe the impossible is possible. Isn’t that the hope we need when CF gets wild? Most adults step carefully in their language for fear of either being too optimistic or pessimistic. When I left my home in Hawaii for California to seek transplant, people were afraid to say it likely would be the last time we’d see each other. Even my pastor admitted thinking that.

However, my pastor’s daughter, Sadie, had confidence she would see me again. According to her mom, she prayed every night that I would return to Hawaii. She didn’t worry about finances, organ rejection, or infections. She only thought that the Bradley she knew — despite all his sarcastic joking directed at her while she painted his nails — was powerful enough to survive, and his God is even more powerful. When I returned to Hawaii last month, two years later, she hugged me so tight that it squeezed tears from my eyes.

Another perk is that when I ignore a kid’s question by changing the topic, they go along with it because they trust you when you make some weird excuse. When a kid asks me if I’ll die early, my response is that my disease won’t kill me. They accept that answer readily. Sadie believed it, so why shouldn’t I?

***

Note: Cystic Fibrosis News Today is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Cystic Fibrosis News Today, or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to cystic fibrosis.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.