3-D Map of CF Protein Structure May Help Determine How Disease Develops

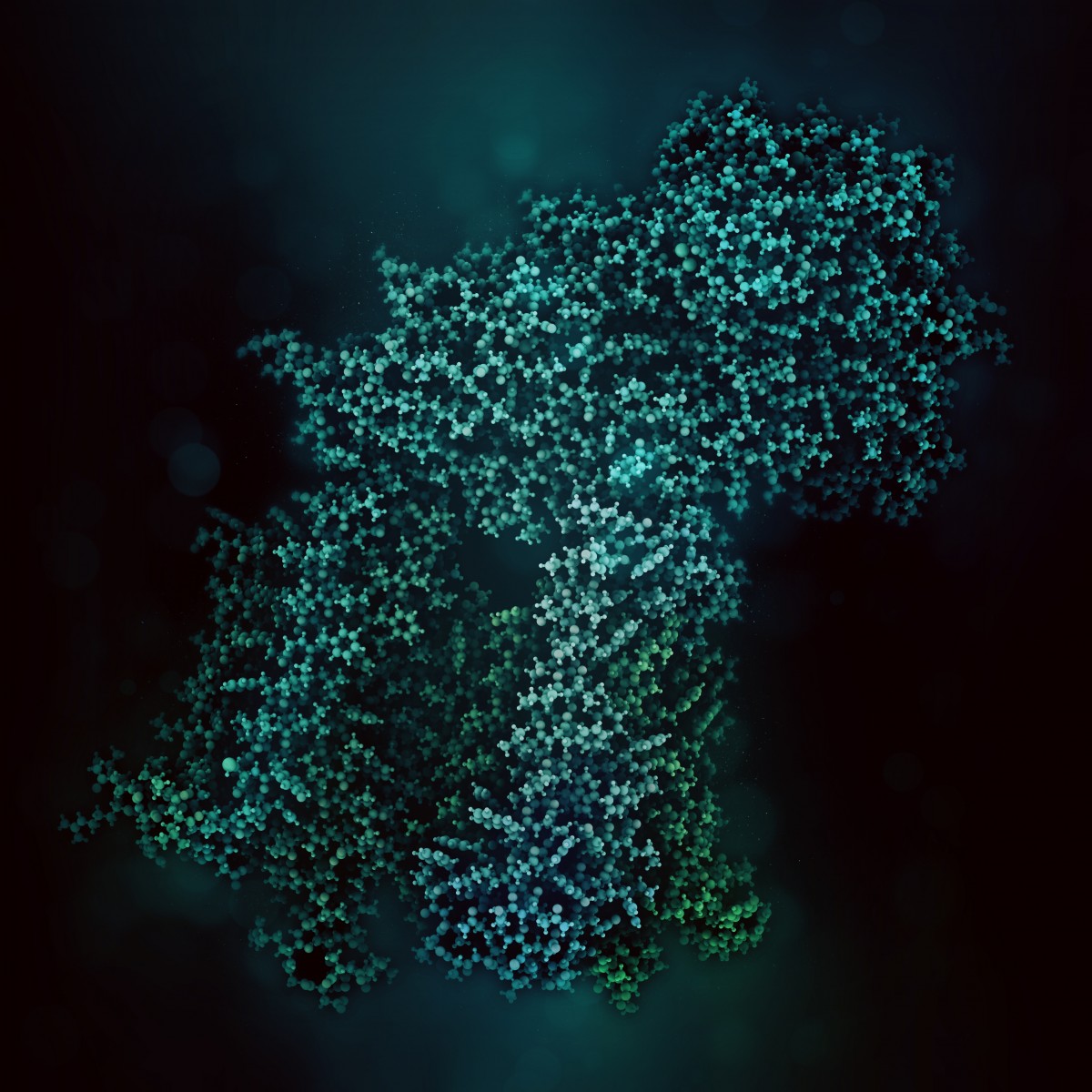

Scientists have identified the three-dimensional structure of the protein responsible for cystic fibrosis (CF), a development that will help them understand how mutations of the protein lead to the disease.

They also found an area in the protein where many disease-causing mutations are located, and a region within that area that is likely to be responsible for most cases of the disease.

The study, “Atomic Structure of the Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator,” was published in the journal Cell.

“With the three-dimensional structure, which we have resolved down to the level of atoms, we can say more about how the cystic fibrosis protein works normally and visualize how it becomes altered in patients,” Dr. Jue Chen, the study’s lead author, said in a press release. He is the William E. Ford Professor and head of the Laboratory of Membrane Biology and Biophysics at Rockefeller University.

By examining the areas where the mutations are located, “we hope it may become possible to devise treatments that correct these errors,” said Dr. Zhe Zhang, the study’s first author.

Scientists have identified hundreds of mutations in the gene that encodes the protein responsible for cystic fibrosis — the CFTR or Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator gene. But they had been unable to understand how the errors impair the gene’s function because until now they had yet to identify the CFTR protein’s structure.

The main obstacle to determining the structure was obtaining crystals of the protein. Chen and Zhang sidestepped that issue by using cryo-electron microscopy to examine protein molecules without having to turn them into crystals.

They took pictures of nearly a million CFTR molecules frozen in a thin layer of ice. Then they assembled the two-dimensional snapshots to give them the first complete three-dimensional structure of the cystic fibrosis protein.

“Seeing the first glimpse of the whole molecule felt like a privilege,” said David Gadsby, the Patrick A. Gerschel Family Professor at Rockefeller University and head of its Laboratory of Cardiac and Membrane Physiology.

“It was fantastic,” he said. “It was as if Mother Nature had finally opened a door that had long been shut.”

The researchers found 46 areas of the protein that can be altered by disease-causing mutations. A surprising finding was that many mutations occurred in just one area.

One of the mutations in that area is responsible for 70% of the cases of the disease. A detailed analysis revealed that this point is particularly vulnerable to disruption.

“We think this is a good place to start looking for ways to treat cystic fibrosis at its source,” said Chen, who is also a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. “If I was a biochemist developing drugs, I would look for something that could act a bit like glue to strengthen this weak point within the protein.”