Antibiotic-resistant Bacteria in Fish Treated by Adding Phage Therapy

Written by |

Kazakov Maksim/Shutterstock

Scientists using phage therapy — specifically a bacteriophage they dubbed “Muddy” — successfully treated an infection by an antibiotic-resistant strain of Mycobacterium abscessus bacteria in a zebrafish model of cystic fibrosis (CF).

For five days, the team treated the zebrafish, which were infected with M. abscessus, a lung-damaging bacteria associated with CF, by using the Muddy phage therapy along with the antibiotic rifabutin.

“With this combination treatment, the fishes’ infections were much less severe; the fishes’ survival rate rocketed to 70%,” the researchers said in a press release. “This is a dramatic improvement compared to fish treated with only the antibiotic, which had a 40% survival rate.”

While much research will need to be done to determine if this combination would work in human patients with CF, the scientists said that, with these early results, “there is hope.”

These findings support “the development of phage therapies and [provide] the first framework towards the development of a pre-clinical platform to assess the most successful phage/antibiotic combinations and predictions prior to testing in M. abscessus patients,” the researchers wrote.

Titled “Mycobacteriophage–antibiotic therapy promotes enhanced clearance of drug-resistant Mycobacterium abscessus,” the study was published in the journal Disease Models & Mechanisms.

M. abscessus grows rapidly, can severely damage lungs, and is often associated with diseases that affect the lungs, particularly CF. Conventional approaches often require prolonged courses of antibiotics — but in many cases, these infections can become resistant to such treatment, making them challenging to eliminate.

Bacteriophages, also called phages, are viruses that target and kill bacteria, and have been considered a potential therapeutic option for antibiotic-resistant infections. They are highly specific to a particular bacteria, meaning they can target that bacteria without affecting patients or local strains of beneficial bacteria, and can prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistance.

Two recent case studies have reported that such phage therapy safely and successfully treated a 12-year-old boy and a 15-year-old girl, both chronically infected with antibiotic-resistant bacteria following lung transplants due to CF. The bacteria cleared in the girl was M. abscessus.

Previously, researchers at the University of Pittsburgh had identified a bacteriophage — which they called “Muddy” — that efficiently killed a strain of M. abscessus in a petri dish (in vitro). The human sample used in the lab was isolated from a CF patient one month after a lung transplant.

Now, in collaboration with scientists at the Université de Montpellier, in France, the team further investigated this type of phage treatment in combination with antibiotics to assess treatment efficiency with combined therapy.

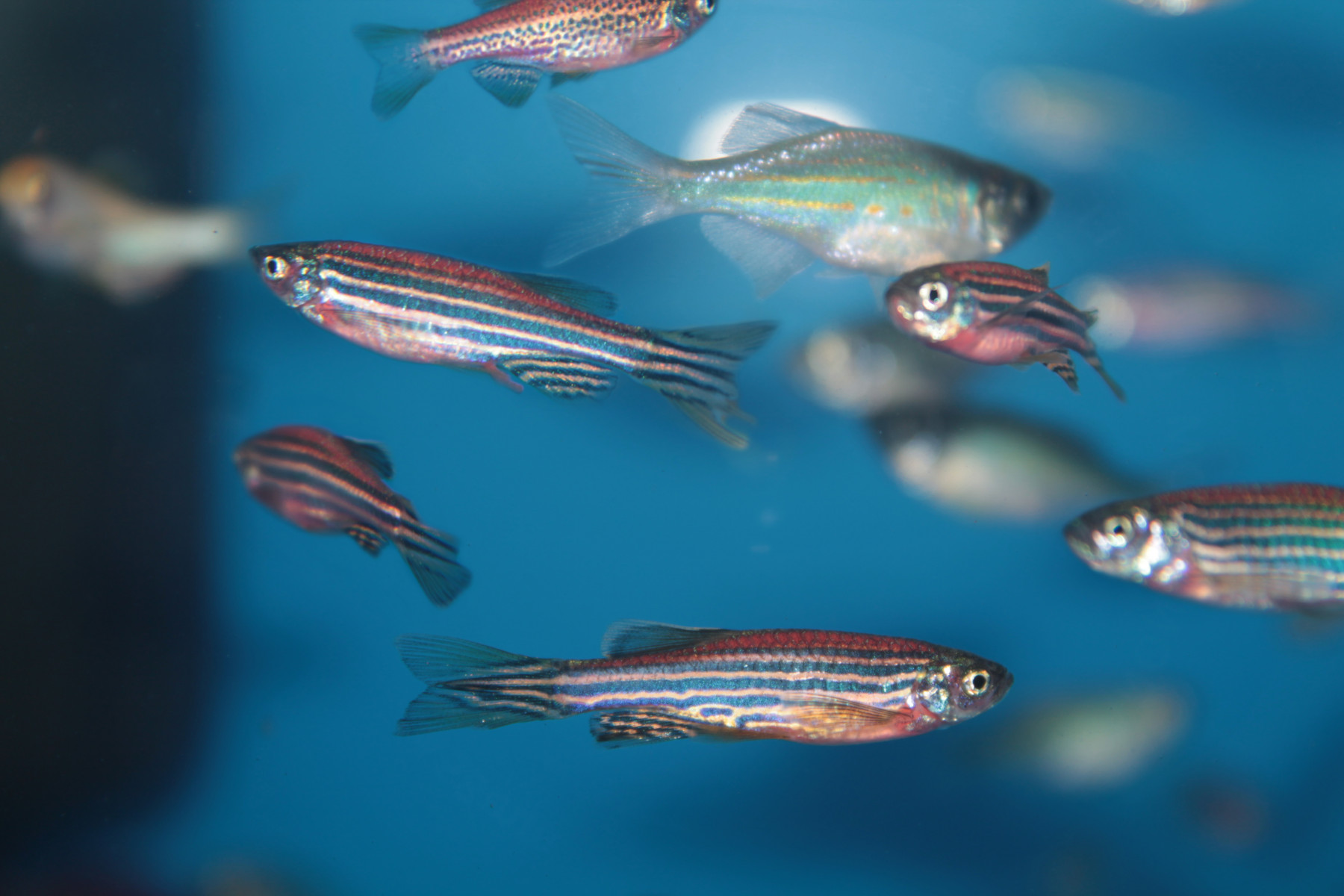

As a model organism, the team selected the zebrafish, which offer advantages in cost, speed, and technical convenience compared with mouse models. Furthermore, bacterial infections in zebrafish mimic some of the same mechanisms seen in humans — thus making them clinically relevant and translatable for human infections.

“We need clinical trials, but there will be many other questions to be answered on our way there […] and zebrafish provide a very helpful tool for advancing these questions,” said Graham Hatfull, PhD, a study co-author from the University of Pittsburgh. Matt Johansen, PhD, a study first author from the Université de Montpellier, added, “We believe that zebrafish will help us understand many bacteriophage-bacteria pairings in our fight against multi-drug resistant pathogens.”

To start, the researchers first tested Muddy, along with a panel of antibiotics, in vitro against the M. abscessus strain isolated from the patient. That bacteria strain had failed to respond to intensive antibiotic treatments.

As expected, Muddy alone suppressed bacteria growth up to a thousand-fold.

Most of the antibiotics also decreased bacteria growth, but adding Muddy further reduced growth with most of the antibiotics tested. One antibiotic in particular, called rifabutin, was found to suppress growth about 100-fold.

When the team combined rifabutin with Muddy, bacteria growth dropped up to 100,000-fold compared with untreated controls.

“These findings indicate that the addition of a wide panel of antimicrobial drugs potentiates the effect of Muddy and vice versa,” the team wrote. “In addition, drug/phage combinations can overcome the limited activity of drugs in antibiotic-resistant isolates.”

After establishing an M. abscessus infection in healthy zebrafish, Muddy alone was injected into the bloodstream. Treatment with Muddy showed a significant reduction in the infection, whereas this effect was less pronounced with a control phage. Additionally, Muddy treatment significantly decreased the number of zebrafish larvae with abscesses — a marker of disease severity, tissue destruction, and acute infection in zebrafish.

Next, zebrafish that carried a CF-causing mutation were infected with M. abscessus. After 12 days, the fish developed serious infections with abscesses, and 20% survived. After five days of Muddy treatment, 40% of fish survived the infection, but it was less severe with fewer abscesses.

Finally, the CF zebrafish were treated with the antibiotic rifabutin alone, with Muddy alone, or a combination of both. On its own, rifabutin was associated with a significant increase in survival compared with untreated CF-fish, similar to treatment with Muddy alone.

Notably, however, Muddy and rifabutin together further increased survival up to 70% as of 12 days after infection. Moreover, this combination was found to reduce bacterial loads and the number of abscesses.

Those findings demonstrate “the improved therapeutic efficacy of the combined treatment with Muddy and [rifabutin] in a CF animal model with disseminated [M. abscessus] infection,” the researchers wrote.

“In summary, our easy-to-use M. abscessus infection model paves the way for studying the outcomes from the triple partner interactions between the phage, the target bacterial pathogen, and host … immunity,” the team wrote.

This study “supports the development of phage therapies,” the researchers concluded.