Wristband Sweat Sensors May Change How CF is Diagnosed

Written by |

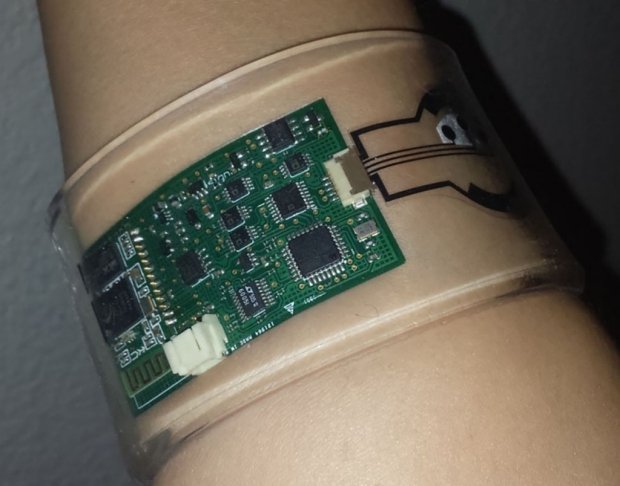

Wearable sensor. Photo credit: Sam Emaminejad/Stanford School of Medicine

Doctors may soon diagnose cystic fibrosis (CF) with the help of a wristband, thanks to a new wearable sweat analysis tool that measures the molecular constituents of sweat, such as chloride ions and glucose.

The device is an upgrade from earlier sweat analysis tools that required patients to be still for up to an hour. It’s significant because this tool lets physicians analyze their patients —generally children — while they’re moving around.

“This is a huge step forward,” Dr. Carlos Milla, the study’s co-author and an associate professor of pediatrics at Stanford University School of Medicine, said in a press release.

The study, “Autonomous sweat extraction and analysis applied to cystic fibrosis and glucose monitoring using a fully integrated wearable platform,” appeared in the journal PNAS.

Sweat analyses are a standard part of the diagnostic procedure since CF causes more chloride ions to accumulate in sweat. But this method of analyzing sweat hasn’t been updated in 70 years. It requires relatively large samples, wired electrodes, and the need for kids to sit still for a long time.

Stanford researchers worked with colleagues at the University of California-Berkeley to develop their new device. To test it, researchers compared a group of CF patients with healthy people.

The wristband consists of sensors and microprocessors, which first stimulate sweat production, then analyze its content. The data is then quickly transferred via cellphone.

“The test happens all at once and in real time, making it much easier for families to have kids evaluated,” said Milla.

The new device might also enable testing of people in remote or underserved communities with limited access to traditional testing equipment, researchers said. The device is so simple to operate, skilled clinicians wouldn’t even have to be there.

“You can get a reading anywhere in the world,” Milla said.

But the scope of the new invention goes beyond diagnosis. Researchers say it can also evaluate the effectiveness of new treatments or help physicians select appropriate treatments in a more personalized manner. In addition, it could ease long-term monitoring of patients’ health.

“CF drugs work on only a fraction of patients,” said Sam Emaminejad, a former Stanford post-doctoral researcher and one of the study’s two co-lead authors. “Just imagine if you use the wearable sweat sensor with people in clinical drug investigations. We could get a much better insight into how their chloride ions go up and down in response to a drug.”

The sensor can also measure the sweat content of glucose to aid in diagnosing diabetes, as well as analysis of many more molecules including sodium, potassium and lactate.

“Sweat is hugely amenable to wearable applications and a rich source of information,” said Stanford biochemistry and genetics professor Ronald Davis, the study’s second co-senior author.

Added Emaminejad, now an assistant professor of electrical engineering at the University of California, Los Angeles: “In the longer term, we want to integrate it into a smartwatch format for broad population monitoring.”