Minorities With CF Have Worse Lung Function, Study Says

Written by |

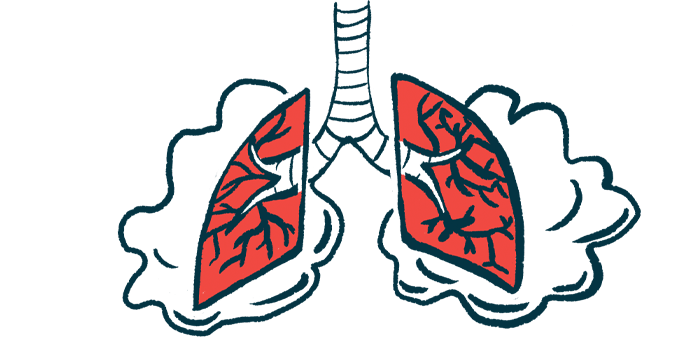

Blacks and Hispanics with cystic fibrosis (CF) have worse lung function than white patients, according to a study from New York City.

However, no differences were found among these groups of patients in several other parameters, including the number of visits to the doctor, treatments with antibiotics, and hospitalizations.

The findings highlight the need to develop culturally appropriate ways of helping CF patients in minority communities, the scientists said.

The study, “Health Disparities among adults cared for at an urban cystic fibrosis program,” was published in the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases.

Although most CF patients are Caucasian, the number of affected patients with other racial and ethnic backgrounds has been increasing over the years. For example, in 2004, 6.1% of people with CF were Hispanic, but by 2019 it increased to 9.4%. Likewise, the proportion of Black CF patients increased from 3.9% to 4.7% from 2004 to 2019.

Previous research has found that people with CF who have a lower socioeconomic status have worse health outcomes. However, the association between racial and ethnic minorities with CF and health status is still uncertain.

For example, the current study found that Hispanic CF patients in California were found to have a 2.8 higher mortality rate than non-Hispanics. However, similar mortality rates were reported in Texas when comparing Hispanics to non-Hispanics.

“This data highlights the fact that there are regional differences in outcomes of minority patients with CF,” the team wrote. “As a CF center in New York City with a relatively large minority population, we sought to determine if racial and ethnic disparities in health outcomes exist and to further understand possible causes for any existing disparities.”

Investigators from Columbia University Irving Medical Center analyzed data from people with CF enrolled in the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry at the University’s Adult CF Program. Patients were seen at least once during 2019. Two main groups were compared: Black/Latinx (BLx) and non-Hispanic Caucasians.

A total of 262 patients were included in the study. Thirty-nine patients (15%) identified as Black or Hispanic/Latinx (BLx). Mean age was 35.9 years for whites and 32.1 years for BLx patients, a difference deemed not statistically significant.

Among whites, 52% were diagnosed before age 2, compared to 46% of BLx patients. BLx participants had a significantly lower median household income based on ZIP code of residence in comparison to whites ($68,485 vs. $102,492).

FEV1, a measure of how much air a person can exhale in one second, was used to assess lung function. In BLx patients, lung function was lower, with a mean FEV1 percent predicted at 59.50, compared to 70.6 in whites.

Mean body mass index, an indicator of body fat, total number of outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and care episodes in which antibiotics were administered into a vein, did not differ between the two groups.

Results revealed an association between minority status and lower FEV1 that trended toward statistical significance.

The F508del mutation in the CFTR gene is the most common disease cause and is linked with worse outcomes. About the same percentage of patients are homozygous for the F508del mutation, meaning the mutation affects both copies of the CTFR gene, or heterozygous, which means it is present in only one copy.

After adjusting for factors such as sex, age, median household income and insurance type, statistical analysis showed that among F508del heterozygous patients, those in the BLx group trended toward lower FEV1 compared to white patients. No such difference was found in F508del homozygous patients or in those without F508 mutations.

“Significant health disparities based on race and ethnicity exist at a single CF center in New York City, despite apparent similarities in access to guideline based care at an accredited CF Center,” the researchers wrote.

“This data confirms the importance of design of culturally appropriate preventative and management strategies to better understand how to direct interventions to this vulnerable population with a rare disease,” they added.

The team noted a few limitations of the study. For example, Black and Hispanic patients were combined in the same category although these are distinct groups. Whether patients were following their treatments as prescribed also was not determined. Also, other factors that may affect health outcomes, including English proficiency and the ability to understand healthcare information, may affect outcomes.