P. Aeruginosa Bacterium May Adapt to Become More Resistant

Written by |

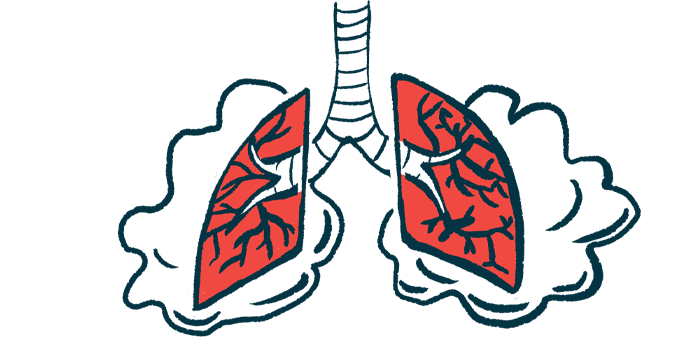

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the most common bacterium infecting the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis (CF), appears to go through a number of changes that enables it to adapt during the course of an infection, a study says.

Using samples of sputum (mucus brought up from the airways by coughing) taken 20 years apart from a patient in New Zealand, researchers found that P. aeruginosa mutated increasingly more often to become more resistant to antibiotics and strengthen its ability to obtain nutrients and form a kind of shelter called a biofilm.

“This research advances understanding of how P. aeruginosa changes to successfully colonize the lung during infection, and may help develop new treatment strategies,” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Genome evolution drives transcriptomic and phenotypic adaptation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa during 20 years of infection,” was published in the journal Microbial Genomics.

The immune system protects the body as it encounters any new or known threats, thus helping fight infections and other diseases. But germs such as bacteria have refined their tactics to try to escape the immune system. An example of such tactics is rapid mutation, which enables bacteria to “disguise” by changing the proteins on their cell surface.

“P. aeruginosa infects the airways of people with CF, impairing lung function, reducing quality of life and shortening life expectancy,” the scientists wrote. “Infections can last for years or even decades, during which time the bacteria adapt and evolve to maximize their survival and growth in the lungs.”

To understand which adaptations occur that make bacteria more resistant, the researchers took samples of sputum from a single patient in 1991 — when he was 26 years old — and again 20 years later.

The patient had two copies of the CF-causing F508del mutation and a chronic infection with P. aeruginosa that did not respond to routine antibiotics. Notably, sputum samples collected later had, on average, higher antibiotic resistance than those collected earlier.

A comparison of the samples taken at the two time points revealed that a genetic bottleneck took place, during which the population of bacteria was reduced greatly in size temporarily, limiting the diversity of the species, only then to take a turn toward great diversification.

This process was accompanied by an average rate of 17 mutations per year, which is higher than the estimated mutation rate for P. aeruginosa in CF of up to 10 mutations per year.

Many of the mutated genes were involved in continued infection and antibiotic resistance. The changes made the bacteria less motile, and increased gene activity related to biofilm formation and more easily obtain nutrients. All this reflected improved survival.

Some of the mutated genes, however, had no known function, “showing that an understanding of how P. aeruginosa evolves during infection in CF is still far from complete,” the researchers wrote.

Other studies have reported multiple mutations linked to antibiotic resistance, but over shorter timescales.

“CF patients acquire a colonizing strain of P. aeruginosa that evolves throughout the course of infection,” the team wrote. “Many of the pathways that underwent mutational change in the patient in this study have also undergone evolutionary change during chronic P. aeruginosa infections in other CF patients.”

More research is expected to shed light on how P. aeruginosa adapts and maintains infection in the lungs of patients with CF.