Nasal microbiome altered in CF infants, new study discovers

Such early alterations may predispose babies to respiratory infections

Written by |

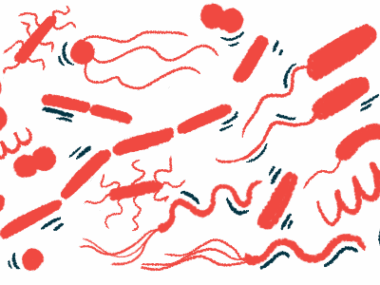

Infants with cystic fibrosis (CF) have alterations to the nasal microbiome — the community of microbes that live in the nose — in the first year of life, a new study has discovered.

These alterations, seen in newborns with CF but not in infants without the genetic disease, may make these children more likely to develop respiratory tract infections, or RTIs, the researchers noted.

Further, additional changes were observed in the CF infants after their first antibiotic treatment and/or infection.

“Early nasal microbiota alterations may reflect predisposition or predispose to RTIs in infants with CF,” the researchers wrote, adding that this “highlights the potential of targeting the nasal microbiota in CF-related RTI management.”

The study, “Early nasal microbiota and subsequent respiratory tract infections in infants with cystic fibrosis,” was published in the journal Communications Medicine.

Scant data on nasal microbiome and links to respiratory infections in CF infants

Due to an abnormal buildup of thick mucus in the lungs — the hallmark symptom of cystic fibrosis — bacteria colonize the airways early in the lives of CF children. This may lead to exacerbations, or a sudden onset of symptoms, followed by antibiotics or hospitalization. Eventually, airway inflammation and structural damage can reduce lung function in people with CF.

Several studies in healthy children have demonstrated a connection between the microbes that reside in the upper airways, or the nose and throat, and susceptibility to lung infections. However, data examining such relationships in infants with CF are scarce.

In previously published work, researchers in Switzerland showed that CF infants had a distinct nose microbiome profile compared with non-CF individuals. Building on these findings, the team now examined associations between the nasal microbiome, RTIs, and antibiotic use in infants with CF.

The researchers recruited 50 CF infants enrolled in the Swiss Cystic Fibrosis Infant Lung Development (SCILD) cohort, a national study assessing early changes in airway function in infants with the condition. To serve as a control group, 30 non-CF infants were included in the study. Both sets of children were examined between three and five weeks after their birth, and followed for the first year of life.

Genetic testing identified the types and abundance of bacteria in nasal swab samples collected in all of the infants over the course of the study. Samples were assessed before the first RTI, before the first antibiotic, after the first antibiotic but before the first RTI, and after the first RTI but before the first antibiotic.

The team calculated both alpha diversity, or the microbial diversity within a sample, and beta diversity, meaning microbial differences between samples, as well as assessing the abundance of several bacterial families.

Analysis finds differences in bacteria seen in CF and healthy infants

An analysis found a higher beta diversity in CF infants than in controls, but only after the first antibiotic, first RTI, or both. Infants with CF also had less stable bacterial communities than controls, as indicated by higher within-patient differences. Again, this difference was absent before the first antibiotic treatment or RTI.

These findings suggest that “the microbiota community destabilizes in infants with CF following first antibiotic therapy and/or RTI compared to control individuals,” the researchers wrote.

Differences in alpha diversity between CF infants and controls could only be found after the first antibiotic treatment but not after the first RTI.

Several families of bacteria were more abundant in CF infants than controls: Staphylococcaceae, Propionibacteriaceae, and Micrococcaceae. Conversely, Carnobacteriaceae and Moraxellaceae were less abundant. At the ages of 4 or 5 months, Staphylococcaceae dominated CF infants, while there were more Carnobacteriaceae and Moraxellaceae in the controls.

The researchers noted that differences in Staphylococcaceae, Micrococcaceae, and Carnobacteriaceae between CF infants and controls were similar before and after the first antibiotic treatment.

Staphylococcaceae and Carnobacteriaceae abundance already differed before the first RTI and after the first antibiotic therapy but before the first RTI. After the first RTI but before the first antibiotic, more Staphylococcaceae were detected in CF infants, according to the researchers.

Targeting nasal microbiota may aid in CF management in children: Study

In the first year of life, CF infants with more RTIs — those experiencing more than three weeks of infection — had lower alpha diversity than those with fewer RTIs, or three weeks or less of infection, before the first antibiotic or RTI. In contrast, the beta diversity did not differ regardless of the number of RTIs. Reduced abundance of Neisseriaceae and Propionibacteriaceae were noted before the first RTI or antibiotic, per the researchers.

Both alpha and beta diversity rose in CF infants after the first antibiotic treatment. Likewise, the families of Neisseriaceae and Propionibacteriaceae bacteria also increased. No association was observed between the number of antibiotic treatments and alpha diversity, beta diversity, or abundance differences. The researchers noted that few infants in the study had more than two courses of antibiotics.

After the first RTI, the beta diversity, but not the alpha diversity, rose in CF infants, “reflecting a larger [diversity] of the microbiota profiles in the CF group after the first infection,” the team wrote. An increase in the abundance of Neisseriaceae after the first RTI was also seen.

[These] results suggest that infants with CF could potentially benefit from treatments that modify microorganisms present in their respiratory tract prior to development of any RTIs [respiratory tract infections], or from different antibiotics to those used by infants without CF.

“We could show that the nasal microbiota is already altered before the first RTI or antibiotic treatment in infants with CF,” the researchers concluded. “It might predispose to a higher number of subsequent RTIs and is not (only) a consequence of recurrent RTIs or of antibiotic treatment in infants with CF.”

Based on these findings, the team suggested that “in the future, targeting the nasal microbiota might … be an attractive option in CF-related RTI management.”

Overall, according to the researchers, these “results suggest that infants with CF could potentially benefit from treatments that modify microorganisms present in their respiratory tract prior to development of any RTI, or from different antibiotics to those used by infants without CF.”