Phage Therapy: Legacy of CF Advocate Mallory Smith Endures

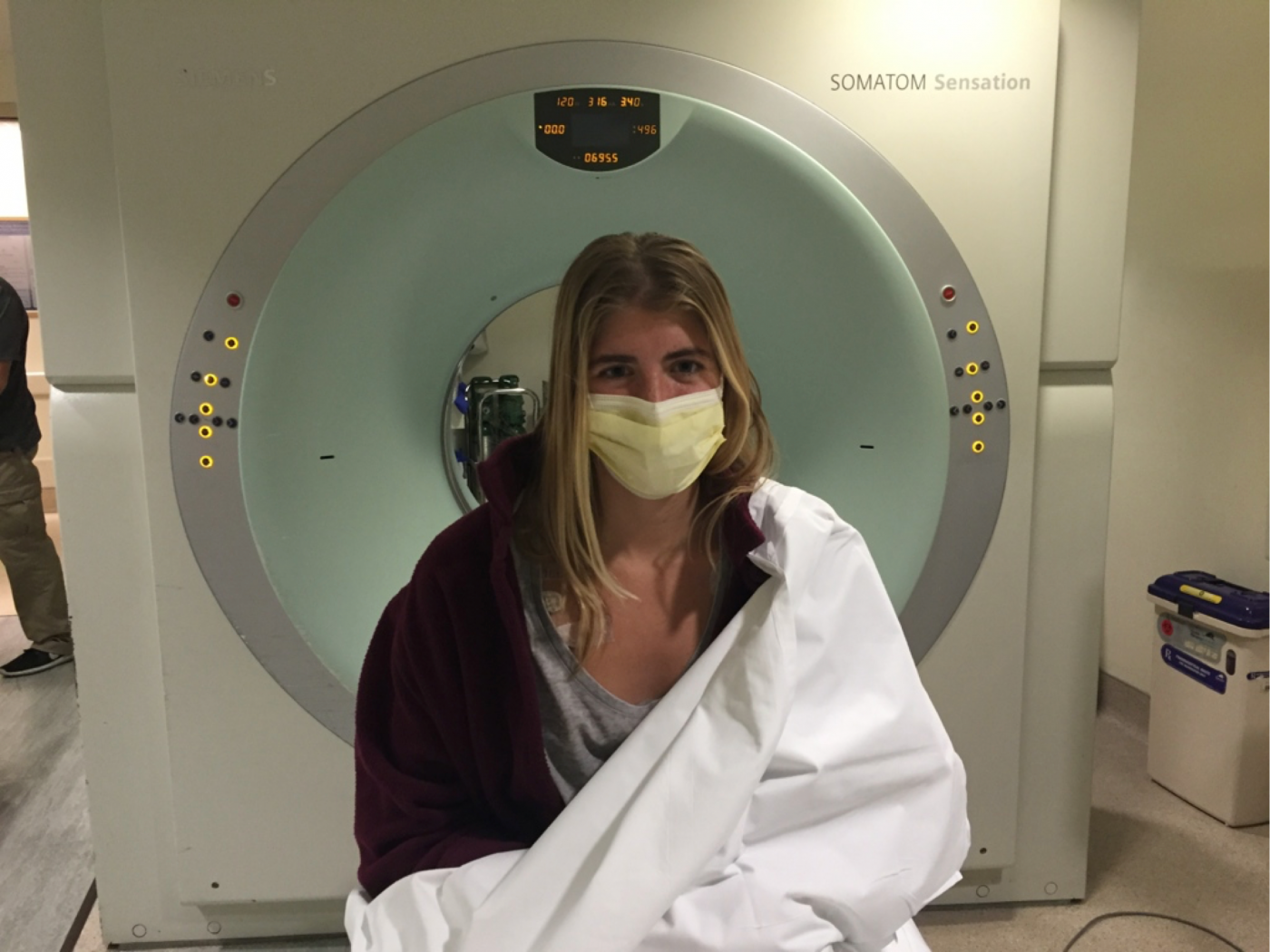

Mallory Smith in front of a CT scanner. (Photo courtesy of Diane Shader Smith)

The legacy of Mallory Smith, who died nearly four years ago from a cystic fibrosis-related superbug infection in her lungs, is living on in the form of raising awareness and funds for a novel treatment called phage therapy that might have saved her life.

Bacteriophages, or simply phages, are viruses that can selectively target and kill bacteria. While still experimental, phage therapy could have important implications for the treatment of cystic fibrosis (CF) when bacteria in patients’ lungs become resistant to antibiotic treatment.

Such was the case for Mallory, a CF patient and the first person to receive phage therapy in 2017 after it was found that the treatment-resistant Burkholderia cepacia superbug she had been battling had moved into her newly transplanted lungs. Unfortunately, by the time the phages were grown, transported, and injected, it was too late, and Mallory died before they could do their work.

Now, Mallory’s mother, Diane Shader Smith, has become a phage therapy evangelist, traveling the country speaking about her daughter’s legacy and how, if given more time, phages created by the U.S. Naval Medical Research Center and Adaptive Phage Therapeutics to attack the B. cepacia bacterial infection in Mallory’s lungs might have saved her life.

“The difference between the impossible and the possible lies in a mother’s determination to preserve her daughter’s life and legacy and share this important treatment that people just don’t seem to want to embrace,” Smith said in a phone interview with Cystic Fibrosis News Today.

In her tireless advocacy, Smith has traveled around the country and given 172 presentations since Mallory’s memoir, “Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life,” came out in March 2019, pivoting to Zoom meetings when COVID-19 forced social distancing. The New York Public Library, Columbia Law School, Facebook, and Stanford Hospital are just a few locations she’s visited.

According to Smith, some CF doctors hadn’t even heard about phages.

“I kept introducing people to phage therapy,” Smith said. “And now they’re finally listening.”

Mallory’s legacy

Advances in the treatment of CF, such as Trikafta and other CFTR modulators, high-frequency chest wall oscillation, antibiotics, and improved transplant medicine, have helped many with the disease live well into adulthood. But for some like Mallory, it wasn’t enough.

“We’ve done these Herculean things to keep the cystic fibrosis patients alive and to have them die from a superbug is just a tragedy,” said epidemiologist Steffanie Strathdee, PhD, now the co-director of the University of California San Diego’s Center for Innovative Phage Applications and Therapeutics (IPATH). Strathdee was instrumental in developing the phages used to try to save Mallory’s life.

But Mallory’s story lives on in her mother, and Smith believes more lives will be saved as she spreads her daughter’s message along with the medical process of phage therapy.

Her work is paying off.

An email exchange, for example, relates how Daniel Layish, an associate professor at the University of Central Florida and co-director of the Central Florida Pulmonary Group Adult Cystic Fibrosis Center, directed one of his patients to receive phage therapy at Yale after hearing Smith’s presentation at his university. Smith recently directed a $25,000 donation to Yale phage research.

Neither Smith nor her husband, Mark, are taking any of the money raised through her speeches, fundraising, or book sales. Instead they are directing it and donors to a fund set up in Mallory’s name and managed by the California Community Foundation, for phage research and ex vivo lung perfusion technology (a technique to keep lungs “alive” during the time before a lung transplant).

Biotech companies also are getting involved, with the possibility of genetically editing phages, and thus the potential to gain a lucrative patent. Smith said Mark pushed Cystic Fibrosis Foundation CEO Michael Boyle, MD, to consider pursuing phage therapy; the foundation now is funding a Phase 1/2 clinical trial (NCT04596319) evaluating Armata Pharmaceuticals’ inhaled phage therapy, known as AP-PA02, for CF patients. The study is still recruiting participants.

In addition, BiomX recently announced it was on track to have results by the end of the year for a Phase 2 trial assessing BX004, its phage therapy candidate for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections in people with CF.

A Phase 1/2 trial (NCT04684641) for a phage therapy called YPT-01 has just started at Yale, and is still recruiting. IPATH plans to start its own phage clinical trial later this year pending approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Mallory’s fund provided the inaugural $100,000 gift to IPATH. Later this year, in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health, the University of California San Diego will launch the first multicenter phage therapy trial in the U.S. Three of the locations where Smith gave speeches — UPMC Hospital in Pittsburgh, University of California San Francisco, and University of California Davis — will be trial sites.

Furthermore, IPATH’s Burkholderia Patient Registry, launched in 2020, is being used to build a library of phages, with research still being done on lung specimens from Mallory.

Smith says that between An Evening in Mallory’s Garden gala, which was started by her family in 1995, and the fundraising since she passed, a total of $5.5 million has been earmarked for CF research.

Why phages?

Phage therapy may be a key to fighting antibiotic-resistant bacteria that have found ways to protect themselves from broad-spectrum antibiotics. They were discovered more than a century ago, but scientific breakthroughs in understanding genetics, the waning shelf life of antibiotics, and stories like Mallory’s are bringing phage therapy research to light.

Phages have been the natural predator of the kind of superbug that killed Mallory. Lytic phages will attach to particular receptors on a bacterium cell, introduce their genetic material into the cell, multiply, and eventually cause the cell to burst.

Phages were discovered in 1915, but scientific hurdles — such as phage purification — caused a delay in phage research.

Bacteriophages aren’t just important in CF. Advances in this therapeutic approach could have world-altering consequences, as bacteria become resistant to even the toughest antibiotics.

In Shanghai, doctors recently used phages to save two patients with critical COVID-19 from an Acinetobacter baumannii bacterial infection. Two other patients in the four-person study died from respiratory failure.

“It’s really the next pandemic that’s facing us, and Mallory’s story helps put a face on that the same way Tom’s does,” Strathdee told CF News Today in a phone interview. Tom is Strathdee’s husband, whose life she saved by using phages after he picked up a deadly virus in Egypt.

‘Salt in My Soul’

Mallory’s posthumously published book, “Salt in My Soul: An Unfinished Life,” comprises her journal writings from age 15 and her last year at age 25. It uncovers the inner struggle of living with CF and helping to spread the word about phage therapy.

According to Smith, the book has sold about 33,000 copies and the National Library of Medicine deemed it its December read. The book exposes Mallory’s fight with CF, battle with mental health, and life as a writer and patient as she kept a positive demeanor around her family and friends.

“[The book] was my lifeline. It gave me a sense of purpose. It helped me keep her alive. It helped me introduce her to the world,” Smith said.

Afflovest, the maker of a mobile airway clearance therapy vest for CF patients, has agreed to donate 150 copies of Mallory’s book to those in the CF community who can’t afford it due to high medical costs. Interested individuals can go to the contact page on the book website to find more information.

Mallory’s influence is still widespread in the CF community. She introduced her friend Emily Kramer-Golinkoff, founder of the nonprofit Emily’s Entourage, to phage therapy. One of the research projects it funded in the latest 2020 grant round was using phages to kill Staphylococcus aureus in the nose and lungs of CF patients.

A documentary about Mallory’s life, produced by 3 Arts Entertainment and Reno Productions, is complete and will be out late this year or early 2022.

Smith, Maryanne O’Hara, who also lost her daughter to CF under similar circumstances; and David Weill, MD, former director of the Center of Advanced Lung Disease and Lung and Heart-Lung Transplant Program at Stanford University Medical Center, will speak in an upcoming lecture series called “Three Perspectives, One Purpose: A Call for Collaboration in Medicine,” starting July 28 at Boston Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a major teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School.

If Mallory’s phages had arrived even two days earlier, Strathdee said, Mallory might have been able to publish her second book and present alongside her mother. But now, other people with CF have been saved by the same treatment Mallory’s family had so tirelessly tried to get to her in time.

“She made history that night,” Smith said.

Researchers published a study in 2019 on an adolescent with CF who was successfully treated with a three-phage cocktail to attack her Mycobacterium abscessus infection, which flared up after her lung transplant.

“I want to create a piece so moving that people are in disbelief,” Mallory writes in the introduction to the final part of her book. “And I want it to be like handing people a pair of glasses, giving them a way of seeing something they didn’t even realize they were seeing.”

And those glasses took the form of a microscope pointed at tiny viruses.