US study examines lung function decline in younger CF patients

Adverse social and environmental factors weigh heavily in findings

Written by |

Various social and environmental factors in different locations across the U.S. influenced a decline in lung function among adolescents and young adults with cystic fibrosis (CF), a large-scale analysis demonstrated.

CF patients with early lung function decline tended to live in areas with more social-environmental adversity, such as higher community deprivation, crime, and air pollution. U.S. locations with the highest social-environmental adversity and peak lung decline levels were Hispanic and rural communities, and densely populated urban areas.

In comparison, middle decliners living with more adversity experienced a rapid decline in lung function months earlier than those with less adversity.

The large-scale study, “Social-environmental phenotypes of rapid cystic fibrosis lung disease progression in adolescents and young adults living in the United States,” was published in the journal Environmental Advances.

In CF, inherited mutations cause the accumulation of abnormally thick and sticky forms of mucus in various organs, particularly the lungs and digestive tract. Excess mucus in the lungs results in inflammation and infection, which leads to a decline in lung function over time.

Emerging evidence suggests that non-genetic factors, such as those found in the environment, like air pollution, play an additional role in lung function decline in CF patients.

Still, “environmental influences on early cystic fibrosis lung disease are not well characterized,” according to a team led by researchers at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio.

So, the researchers conducted a comprehensive study to investigate environmental-related characteristics (phenotypes) associated with rapid lung function decline in people with CF.

Using the U.S. CF Foundation Patient Registry, routine health measure data were collected on 24,228 CF patients (51% male), ages 6-21 years. Most patients carried at least one copy of F508del, the most common CF-causing mutation. The prevalence of infections, CF-related diabetes, CFTR modulator use, and smoking increased over time.

Calculating a social-environmental adversity score

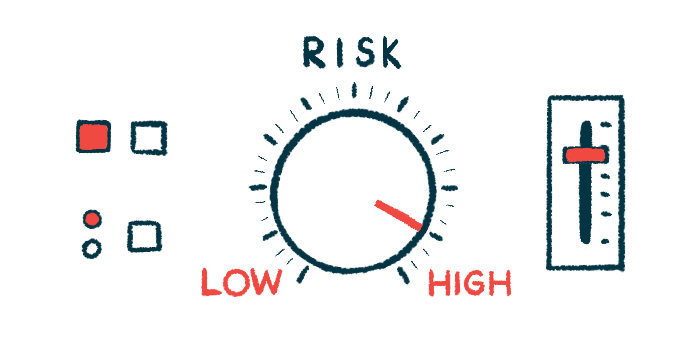

The team applied ZIP codes to assess location-specific social and environmental factors (geomarkers), such as air pollution, green space, crime, and socioeconomic deprivation. From these data, a social-environmental adversity score was calculated and compared with lung function decline over time, with higher scores indicating a more negative social environment.

Social-environmental adversity scores were driven primarily by crime, land cover, air pollution from traffic, and density and length of primary and secondary roadways. Higher adversity scores were associated with a more rapid decline in lung function with age, data showed.

Researchers then classified CF individuals into three distinct social-environmental phenotypes of rapid lung decline over age: early, middle, or late.

Patients with early lung decline experienced similar timing and extent of such decline regardless of social-environmental adversity. Middle decliners with more adversity experienced a decline 1.2 years earlier, on average, than those with lower adversity. Meanwhile, late decliners with lower adversity had a slightly earlier peak decline in lung function than their higher adversity counterparts.

Specific geomarkers made a difference

Specific geomarkers drove the differences in social-environmental adversity among patients with early, middle, and late lung decline. Early decliners lived in areas with higher community deprivation, crime, air pollution, and surfaces impervious to water flow (like pavement). Middle decliners lived closer to longer and denser secondary roadways than late decliners.

Mapping the estimated peak decline and social-environmental adversity across the contiguous U.S. showed the most severe lung declines and greatest adversity occurred in western and southern regions. Areas with the highest social-environmental adversity and peak decline levels corresponded to Hispanic centers, rural communities, and densely populated urban areas. At the same time, the central Plains had lower adversity, but higher peak declines.

Differences in early, middle and late decliners

Middle decliners, who were slightly older with lower initial lung function, were more often male, had two F508del copies, and were smokers. They also had the highest use of pancreatic enzymes and the approved CFTR modulator Orkambi (ivacaftor/lumacaftor).

Early decliners were more likely to have no insurance or public insurance or CF-related diabetes. Although this group had the lowest rates of pulmonary exacerbations — the sudden worsening of lung symptoms — they had the highest rates of lung infections, hospitalizations, lung transplants, and mortality. Late decliners had the highest prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance, which can lead to CF-related diabetes, and used Kalydeco (ivacaftor) more often.

Researchers then identified strategies for maintaining lung function in combination with social and environmental health interventions. More frequent screening for social needs could be made available to CF patients who live in communities with high crime rates or deprivation. Also, the impact of air pollution can be mitigated by HEPA filters in the home or via smog alerts during spikes in air pollution.

Because of higher within-area variation compared to between areas, people with CF and their families who make long-distance moves to different locations may still be at risk of rapid lung decline if the social-environmental adversity is similar. Still, relocating within the same area to a community with less social-environmental adversity may lower the risk of decline.

“The present study offers a comprehensive profile of geographic exposure risks,” the researchers concluded. It also detailed “how individuals with mild to moderate amounts of lung disease who are subject to adverse social-environmental exposures may maximally benefit from personalized (rather than primary or global) environmental health interventions.”