Window for More Effective Treatment of CF Lung Infections is 2 to 3 Years, Study Suggests

Written by |

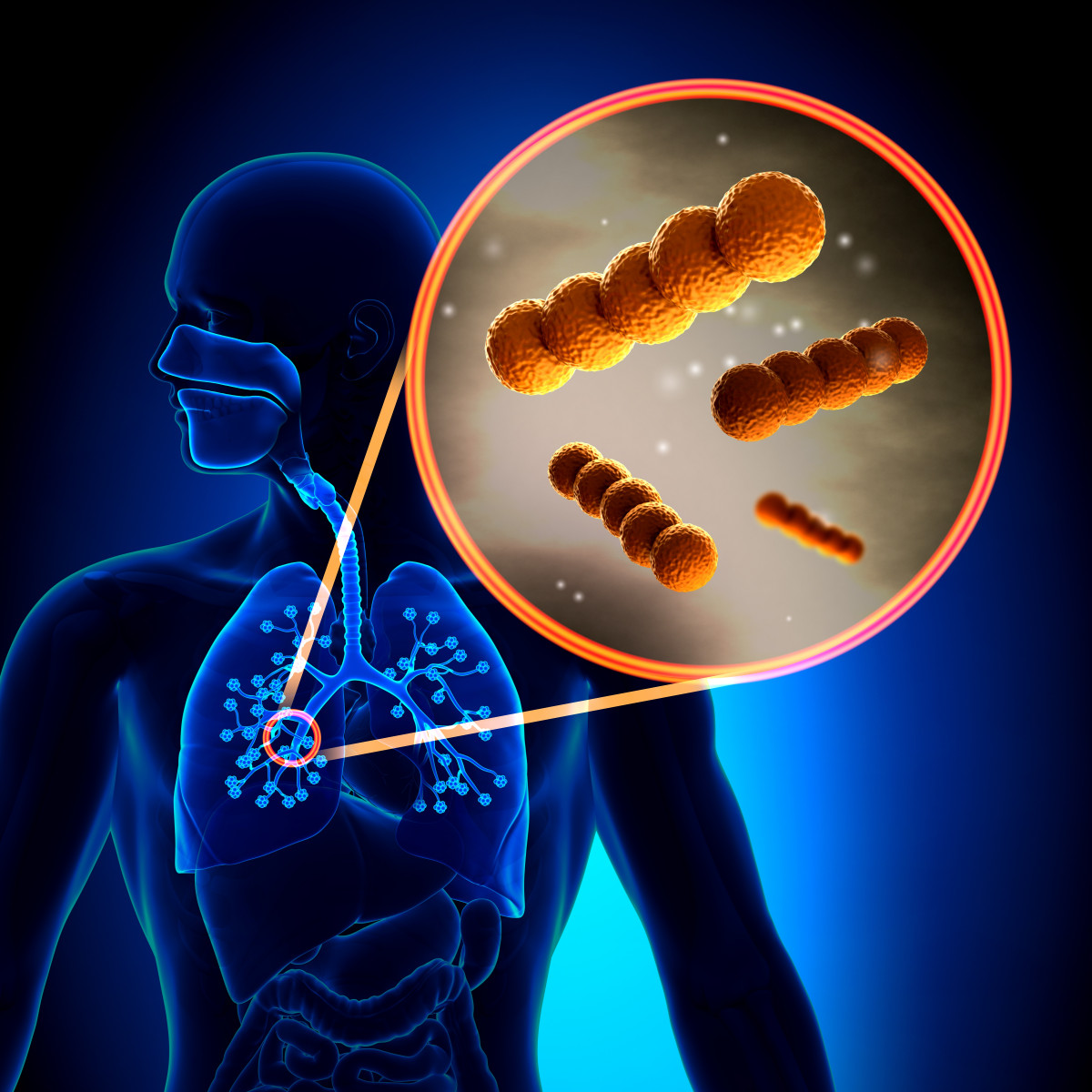

Treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lung infections in cystic fibrosis (CF) patients could be more effective if done within a crucial two- to three-year period when the bacteria are still susceptible to antibiotics, according to a study.

The study, “Evolutionary highways to persistent bacterial infection,” was published in the journal Nature Communications.

Genetic changes that have accumulated over a long period of time have contributed to the increased ability of bacteria to adapt to new environments. There is a lot of diversity among bacteria in chronic CF infections, but researchers have previously agreed that increased antibiotic resistance or loss of virulence — the ability to cause disease — will ultimately occur regardless of the particular bacterial population.

Although genetic adaptations associated with colonization of a host have been identified in CF pathogens, few studies have looked at bacterial phenotypes, meaning the cumulative impact of mutations. There have also not been very many studies that have assessed the early stages of infection, when bacterial strains — often P. aeruginosa — become successful pathogens in the lungs of CF patients.

To better understand pathogen adaptation to the host, researchers from Denmark used statistical methods that account for the body’s effects on bacterial lineages and assessed their adaptive paths.

Discuss the latest research in the Cystic Fibrosis News Today forums!

They screened 443 P. aeruginosa airway isolates from 39 young patients with CF (median age at first P. aeruginosa isolate of 8.1 years), all of whom were treated at the Copenhagen CF Centre at Rigshospitalet, over a 10-year period.

This approach was different from that of most studies, which typically looked at older CF patients with chronic infections, which have already become multidrug-resistant. According to the authors, this research “fills the critical gap between studies of acute infections and chronic infections.”

Results revealed that P. aeruginosa rapidly adapted within two to three years after infection, a period in which they showed little antibiotic resistance. The bacteria then grew slower and reduced their susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, an antibiotic commonly used as first-line treatment in CF.

“This means that one should pay extra close attention in this period of time to avoid the infection becoming persistent,” Jennifer Bartell, PhD, a researcher at The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability, Technical University in Denmark and one of the study’s co-first authors, said in a press release.

“In this early phase, the bacteria change a lot and become much more robust, but the doctors do not necessarily see this with current clinical measurements,” said Lea Sommer, PhD, from the Rigshospitalet and co-first author of the study.

Although growth rate and ciprofloxacin resistance were relevant for the persistence of bacterial infections across all patients, the group still showed remarkable diversity. This variability in bacterial population and modes of adaptation contributes to pathogen persistence in the airways, according to the investigators. The findings also support the idea that bacterial adaptation is patient-specific, and is influenced by specific mutations and genetic background.

According to the team, treatment resistance is independent of whether or not the bacterial strains are mucoid — a trait characterized by the production of a protective, slimy coating and associated with greater difficulty in fighting the pathogen and accelerated loss of lung function.

In contrast, traits such as the ability to attach to surfaces evolve more consistently in persisting infections, and could be a better early marker of chronic infection.

“We can see which traits might actually be valuable for the clinicians to monitor in addition to antibiotic resistance,” Sommer said.

The team is now planning to assess bacterial response to a larger panel of antibiotics, which could help categorize and better treat infections through personalized approaches in patients with persistent infections, including those with CF.

“In the clinic, doctors would potentially be able to take a single patient’s bacterial screening data and analyze how this patient responds to the current treatment,” Bartell said. “As we gain experience with more patients, it will be easier to assess what can be done to stop the transition to chronic infection.”