Heart failure medication may ease CF-related liver disease: Study

Rabbits treated with sotagliflozin lived longer than those not treated

Written by |

Sotagliflozin, an oral medication approved in the U.S. under the brand name Inpefa as a broadly used treatment for heart failure, may ease symptoms of liver disease related to cystic fibrosis (CF), according to a study in rabbits.

While it’s still too early to tell if sotagliflozin will work in people with CF, data from the preclinical study suggest that it may be a candidate to reduce inflammation, scarring, and the buildup of fat in the liver.

The study, “Sotagliflozin attenuates liver associated disorders in cystic fibrosis rabbits,” was published in JCI Insight.

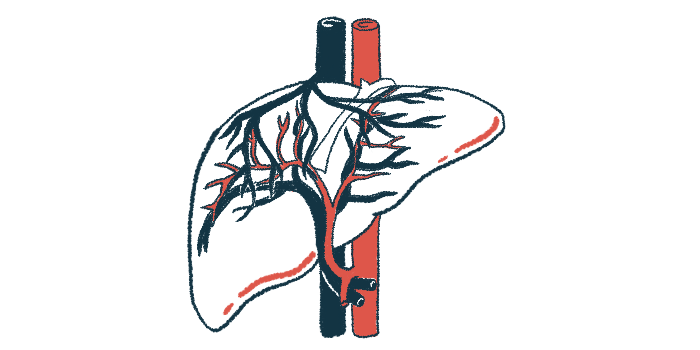

CF occurs when a protein called CFTR is faulty or missing, causing thick mucus to build up in the organs. The mucus can block the bile ducts, thin tubes that carry bile away from the liver to help break down fats in the small intestine.

As bile flow is slowed or stopped, bile builds in the liver, causing inflammation and scarring. Left untreated, scarring can become permanent and cause cirrhosis, a condition in which the liver stops working because its healthy tissue has been replaced by scar tissue.

Protein in cells points to liver disease link

Building on the discovery that SGLT1, a protein that transports sugar and sodium into cells, was abundant in liver cells of a rabbit model of CF, researchers tested whether sotagliflozin might ease symptoms of liver disease.

Sotagliflozin blocks the action of SGLT1, reducing the amount of sugar that’s taken into the bloodstream. It also blocks another sodium/glucose cotransporter, SGLT2, in the kidneys, increasing the amount of sugar that’s passed out through the urine.

Together, these actions lower sugar levels in the blood and increase the elimination of salt and water in the urine. Sotagliflozin is approved in the U.S. to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death and worsening heart failure events in certain adults.

The researchers turned to rabbits missing part of the gene coding for the CFTR protein, causing them to develop symptoms, such as breathing problems, liver disease, and poor growth and bowel blockages, seen in people with CF.

Treated rabbits ate more, lived longer

CF rabbits treated with oral capsules of sotagliflozin starting at about 60 days old lived longer than untreated CF rabbits. The proportion of CF rabbits that lived 150 days or longer was higher among those treated with sotagliflozin (67% vs. 14%).

Treatment with sotagliflozin also promoted appetite, which translated into faster growth. CF rabbits weighed an average 13.9% more after six weeks of daily treatment with sotagliflozin compared with untreated CF rabbits.

Sotagliflozin resulted in less scarring and inflammation in the liver, and increased the amount of glycogen, a sugar molecule stored in the liver when the body doesn’t need all the sugar available.

In untreated CF rabbits, viscous mucus blocked the bile ducts, causing scarring and cirrhosis. In those treated with sotagliflozin, mucus was not as viscous, and there were fewer signs of scarring and cirrhosis around the bile ducts.

Sotagliflozin also reduced elevated endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress responses in the liver and other organs. The endoplasmic reticulum is a structure in cells that’s involved in protein production. ER stress can occur when there is an imbalance in protein processing.

The findings suggest that sotagliflozin may be repurposed to treat CF-related liver disease related to CF, though further research is needed to confirm the findings and test how safe sotagliflozin is and how well it works in people with CF, the researchers said. “Our work merits future preclinical and clinical evaluations,” they wrote.