Ultrasound found to ID CF children at increased risk of liver disease

But study shows it's hard even for experts to interpret image results

Images taken via an ultrasound of the liver can be used to identify children with cystic fibrosis (CF) who may be at increased risk for advanced liver disease, a new study reports.

“We have demonstrated that research-based [ultrasound] screening of children with CF can identify children with a high risk for the development of advanced CF liver disease,” the scientists wrote.

However, it’s likely not yet possible for a liver ultrasound to be used as a prognostic tool in the clinic, the team noted.

“There should be caution in translating these results, from specially trained radiologists and ultrasound technicians to the clinical setting where there are ranges in experience and more individuals are involved,” the researchers wrote.

The study, “Heterogeneous liver on research ultrasound identifies children with cystic fibrosis at high risk of advanced liver disease,” was published in the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. The work was funded by the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

Normal ultrasound findings linked to low likelihood of liver disease

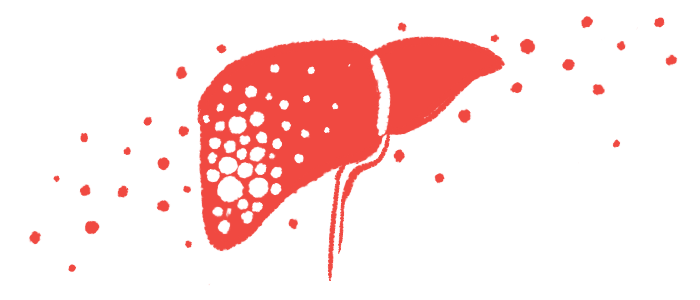

About 7% of CF patients will develop advanced cystic fibrosis liver disease, known as aCFLD. The disorder is characterized by liver scarring called cirrhosis, nodules or growths on the liver, and high blood pressure in the portal vein that leads to the liver.

aCFLD with cirrhosis tends to develop in late childhood or adolescence in CF and disproportionately affects male patients and those with class 1, 2, or 3 mutations.

Despite advances, it remains difficult to predict the risk of aCFLD for an individual patient.

Early studies have suggested that an ultrasound of the liver may help detect early signs of aCFLD. The liver normally looks smooth on ultrasound imaging, but some patients have a patchier pattern, referred to as a heterogeneous echogenic liver pattern (HTG). Some studies have suggested that patients with HTG are more likely to develop aCFLD.

Spurred by early research, scientists launched a clinical trial called the Prospective Study of Ultrasound to Predict Hepatic Cirrhosis in CF or PUSH (NCT01144507) to test whether HTG, when found on a liver ultrasound, may be a useful marker to identify patients at risk of aCFLD in clinical practice.

The study enrolled 774 children with CF, ages 3 to 12, at sites in the U.S. and Canada. All of the children underwent an initial liver ultrasound that was reviewed by multiple experts for evidence of HTG.

The analysis included data for 55 children with HTG on the initial liver ultrasound, and another group of 116 children with normal liver ultrasound, who were matched according to age and other factors.

Over a follow-up of six years, about one-third (32.7%) of the children with HTG developed aCFLD, as evidenced by newly developed nodules visible on later liver ultrasounds. By contrast, just four (3.4%) of the children with normal liver ultrasound developed aCFLD.

Statistically, these results suggest that children with the HTG pattern on liver ultrasound have a roughly 33% risk of developing aCFLD. Meanwhile, children with a normal liver ultrasound have a 96% chance of not developing the liver disorder.

Put another way, children with the HTG pattern are at nearly 10 times higher risk of aCFLD, according to the team.

“The isolated finding of HTG is associated with a 9.5-fold increased risk for the development of [liver disease] compared with [normal liver findings,] over just a 6-year period,” the researchers wrote.

Further, “most of the HTG participants who develop [liver disease] do so by 5-6 years after the identification of HTG,” they noted.

The team added that “it is also notable that the finding of a [normal liver] pattern had a very low risk for the development of” aCFLD.

Use of liver ultrasound may ID children for potential clinical trials

Among children with HTG, those who developed aCFLD tended to be younger at their initial ultrasound assessment, the study found. These patients also tended to have higher values on a laboratory test called the GPR (gamma glutamyl transpeptidase to platelet count ratio), useful in the diagnosis of forms of scarring

The scientists showed that statistical models incorporating age and GPR values could further improve the predictive power of HTG to estimate aCFLD risk.

While our results will require further study in the clinical realm, they already have potential to identify children with a high risk for aCFLD in future clinical trials.

But a notable drawback of liver ultrasound, the researchers said, is that it can be hard to interpret results — which is why multiple experts reviewed the findings for each patient in this study.

Even then, the experts were markedly less accurate individually than as a group.

“Individual clinical [ultrasound] readings did not perform nearly as well as consensus reads in this study,” the researchers wrote, noting their experts were “radiologists who underwent specific training and who were blinded to clinical data.”

Given this drawback, the researchers stressed that liver ultrasound may not yet be viable as a tool to use in day-to-day clinical practice.

Nonetheless, these findings may be very useful for identifying high-risk patients to participate in clinical trials testing experimental treatments that aim to stop the development of liver disease.

“While our results will require further study in the clinical realm, they already have potential to identify children with a high risk for aCFLD in future clinical trials,” the team wrote.