Real Stories: Recognizing and Reducing the Burden of Cystic Fibrosis Treatments

Written by |

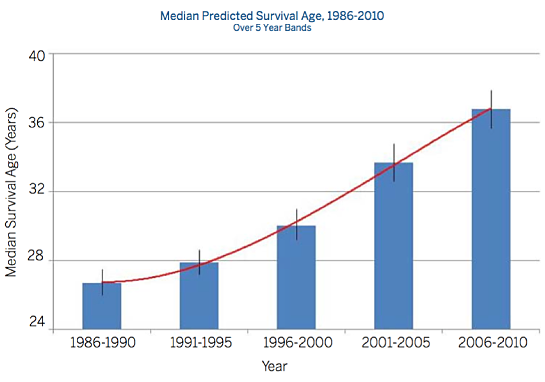

Huge strides have been made in the treatment and management of cystic fibrosis (CF) in the past several decades. According to the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), in 1962 the predicted median survival for cystic fibrosis patients was about 10 years, with few surviving into their teenage years. By the 1980s, people diagnosed with CF still typically had a life expectancy of less than 20 years, and even a decade ago, average life expectancy for a person with cystic fibrosis was only 25 years.

However, thanks to advances such as new medications designed to slow disease progression and mechanical chest physical therapy devices that loosen mucus and make it easier for patients to clear their lungs, today the median projected age of survival for a person born with cystic fibrosis is 41 years, and some people with the disease are living into their late 40s or 50s, although the median age of death is still 27 years.

A 2014 observational death registration study published in the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis reported that the rate of cystic fibrosis life expectancy improvement now exceeds that of the general population.

The authors concluded in the article, “Overall, the improvement in survival witnessed among those with CF in absolute terms, in those countries studied, is considerable and supports the assertion that a median survival in excess of 50 years for those born in 2000 should be expected.”

Graphic credit: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry Annual Data Report 2010

More than 90 percent of all cystic fibrosis patients die of respiratory failure, and lung transplantation has also become an alternative for the treatment of CF patients with severe lung damage.

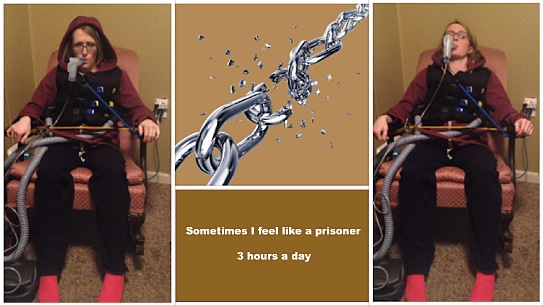

So there is progress in improving both life expectancy and the quality of life for persons burdened with CF. But the advances in CF treatment and management, while welcome, still fall well short of a cure. Life for many struggling with the disease involves the enervating monotony of spending several hours every day sitting down, often isolated, wearing a bulky vibrating chest wall oscillation vest, and inhaling medications through a nebulizer or inhaler mouthpiece three times a day, 365 days a year, to keep their lungs clear of mucus buildup caused by a CF-causing defect in the chloride channel of human cells known as the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) — which is critical for adequate hydration of the lungs and other organs of the body.

Treatment time for cystic fibrosis patients can be uncomfortable, lonely, and boring, and the burden associated is growing as new medications are added, providing benefits but demanding additional time and a greater degree of sacrifice.

This state of affairs has many cystic fibrosis patients questioning whether there is potential for less onerous alternatives to the standard regimen, with more of them taking matters into their own hands — for example, to determine whether good old-fashioned exercise can replace at least one traditional airway clearance session per day, thereby unleashing them from the encumbrances of vests and nebulizers and allowing them to run free, bicycle, play sports, and more.

Freeing CF patients from just that one daily treatment would be equivalent to five weeks of vacation time annually.

Through exercise, some members of the CysticLife.org online CF community have made dramatic comebacks after major health setbacks to their lung function. However, proven scientific knowledge is needed to determine whether exercise can be used as a long-term solution, and as a safe and proven alternative for doctors to recommend to their patients.

Research from a poll CysticLife conducted in late 2014 showed members were most interested in ways to reduce the treatment burden to improve their quality of life. Exercise topped the list as a potentially viable alternative. “Sadly, no one wants to fund this kind of research,” said CF patient and CysticLife.org founder Ronnie Sharpe. “There is no financial incentive for companies to research this topic, so cystic fibrosis patients are on their own.”

Research from a poll CysticLife conducted in late 2014 showed members were most interested in ways to reduce the treatment burden to improve their quality of life. Exercise topped the list as a potentially viable alternative. “Sadly, no one wants to fund this kind of research,” said CF patient and CysticLife.org founder Ronnie Sharpe. “There is no financial incentive for companies to research this topic, so cystic fibrosis patients are on their own.”

CysticLife has partnered with researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, to conduct the world’s largest cystic fibrosis exercise study, enlisting the help of researchers and clinicians from around the country, including at Stanford and Johns Hopkins universities (https://cysticlife.org/researchpolling.php). The final step is to raise the $250,000 required to conduct the study, an objective toward which the community is well on its way.

CysticLife has partnered with researchers at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, to conduct the world’s largest cystic fibrosis exercise study, enlisting the help of researchers and clinicians from around the country, including at Stanford and Johns Hopkins universities (https://cysticlife.org/researchpolling.php). The final step is to raise the $250,000 required to conduct the study, an objective toward which the community is well on its way.

Courtney Wheatley, a postdoctoral Fellow in the Cardiovascular Research Lab of Bruce Johnson at the Mayo Clinic and an Exercise Research Committee member, has agreed to act as principal investigator for the research. Wheatley is a passionate advocate for both exercise and the cystic fibrosis community, and has been involved in cutting-edge research in the category: The topic of her doctoral dissertation was “The Endogenous and Exogenous Regulation of Exhaled Ions in Patients with Cystic Fibrosis.”

“CF patients are in desperate need for alternatives to the existing treatment options. Exercise is a very compelling option that we need to investigate,” Wheatley said on the CysticLife site.

This first research study is part of a larger CysticLife initiative to ensure the voices of cystic fibrosis patients are heard in the research community. CysticLife’s research priorities are set by the community of patients and families, and based on their input.

The CysticLife Research Advisory Board will focus on alternative therapies and nutrition options that can reduce the treatment burden and improve quality of life, especially alternatives that are currently not being studied but if understood, could improve patient care today.

With the help of its technology partner Althea Health, CysticLife is also pioneering ways to make research in home participation more accessible to all CF patients. Through use of communication devices and video conferencing, exercise research volunteers will participate in the research study from home, removing the cost, time delay, and limitations that setting up multiple clinical sites imposes on the research process.

For some first-hand perspective on what living with the burden of cystic fibrosis treatment is really like, Cystic Fibrosis News Today reached out to three individuals who are actively involved with the CysticLife community and the Unleashus campaign — two of whom are personally invested in exercise as a CF therapy — inviting them to share their thoughts and experiences on a range of topics related to meeting and overcoming the relentless day-to-day challenges of coping with cystic fibrosis.

Dr. Julie Desch is a medical doctor, certified personal trainer, and licensed wellness coach who has been diagnosed with CF since birth. Desch founded New Day Wellness in 2005, a nonprofit dedicated to improving the lives of people with chronic illness through health and wellness at low cost and with minimal overhead. She is also publisher and editor of the Sick and Happy blog for people with cystic fibrosis who are interested in optimizing their wellness and happiness, and writer of a Wellness column for the CF Roundtable, a quarterly publication for USACFA (United States Adult Cystic Fibrosis Association).

Pepsi Umberger is a CF patient, a professor of kinesiology at Penn State University, and co-owner with her husband of Balance Fitness in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She is also mother of a 2-year-old.

Tara, who prefers that only her first name be used in this article, is a working mother of a child with cystic fibrosis.

“It would be fantastic to find a way to reduce time sitting tethered to a vest, sucking away at nebulized medicines,” Desch said. “Even when you combine the two — and most people do — two to four (or more if you are sick) treatments each day is an incredible treatment burden. I’m not complaining; after all, this regimen is why I am alive today. But the idea of freeing up some time to DO MORE LIVING, rather than just staying alive, would be awesome.”

“It would be fantastic to find a way to reduce time sitting tethered to a vest, sucking away at nebulized medicines,” Desch said. “Even when you combine the two — and most people do — two to four (or more if you are sick) treatments each day is an incredible treatment burden. I’m not complaining; after all, this regimen is why I am alive today. But the idea of freeing up some time to DO MORE LIVING, rather than just staying alive, would be awesome.”

“Scheduling life around treatments is a drag,” Desch adds. “I almost never miss a treatment, so this has become second nature so much that I don’t even think about it, but when forced to (for this interview), I realize how much my life revolves around treatments. My morning is completely filled. If I did have a job where I had to go to an office, I would need to wake up at 5 a.m. to get it all done before I left. This of course would mean I would need to go to bed at at least 9 p.m. the night before… How fun!

“Fortunately, I am retired, so my morning is mine,” Desch said. “After my son leaves for school, I spend about 90 minutes on therapy, another 30 or so eating, another 30 (or more) dealing with the … uh … consequences of eating (digestive issues are common and no fun), 30 minutes meditating (my preferred stress reduction technique), and 30-60 minutes stretching/doing yoga/mobility type exercises.

“You could argue that the last two are not CF-related, but I would defeat you in that argument. CF is stressful, as a very high incidence of depression and anxiety in our population attests to, and finding a way to deal with it healthfully is a very necessary part of the ‘healthcare’ regimen,” Desch said. “Additionally, coughing and chronic lung disease leads to a lot of chest wall anatomic changes, which lead to many chronic pain issues, not just in the upper back, but downstream in the low back and hips. A stretching/mobility program is a must, and I adhere to mine religiously. So, that adds up to about four hours. Morning over …”

Desch continues: “An afternoon treatment interrupts whatever I need to do later in the day. One of these things is a trip to the gym, where I spend about 90 minutes doing cardio plus weight training. I do moderate cardio exercise, because it works essentially as another treatment, loosening up mucus and forcing me, due to the deep and rapid breathing necessitated, to cough it up. It takes remarkable discipline to keep this up day after day, especially when sometimes, no matter how hard you work at fending it off, CF will creep up and you’ll find yourself in the hospital with pneumonia.”

Umberger stressed the importance of medicine. “I feel like the commitment to staying healthy cannot be discussed without talking about compliance of medicine and therapy,” Umberger said. “I think we all try to come up with creative ways to get our medicines done and still be ‘normal’. I have an hour commute to work, so I do my inhaled therapies during my commute. This buys me extra time in my day, so I gain an hour and a half of free time.

“I have a 2-year-old, so being hooked up to my vest, using a percussor or flutter for an hour, is not always feasible,” Umberger said. “I started using exercise in college to clear out my lungs so I could feel normal and get in my ‘exercise therapy’. My husband and I own a gym, so it is nice to be able to go to the gym and work out and cough and not fear what people will think of me.

“On a good day everything works out the way we plan it,” she said, “an hour of the treatment in the morning and an hour in the evening. Of course that is normal treatments: inhaled antibiotics, pills, and airway clearance. When it is time for IV [intravenous] antibiotics it is an entirely different mindset of time management — eating, sleeping, normal treatments, and still trying to have the energy to work. My job as a kinesiology instructor requires me to move, instruct exercise, and be motivating. Usually once a year I have to explain to my students that I have an IV in my arm and why.”

Tara, whose child has CF, agrees. “Treatments are definitely burdensome. My husband and I don’t have any other children, so we didn’t fully realize how much greater the burden was compared to normal parenting for awhile. But as a babysitter put it, we are basically still on a newborn-type of schedule, as my son needs something every hour or two all day, between meals, vests, and nebulizers. It blew our minds to realize that other families only deal with this schedule for a few months while we are approaching four years. No wonder some of my son’s friends already have younger siblings.”

Speaking of kids and how CF parents have to argue with their children to persuade them to follow their treatment schedules, Desch recalled that her parents never had to fight too much with her because when she was young there were no breathing treatments available.

Now, at 55, she recalls her parents forcing her sister and brother, who also had cystic fibrosis and have since died, to sleep in “mist tents” and do postural drainage, with her parents hitting their backs multiple times a day.

“They didn’t like it and argued a bit,” she said, “but they were also very sick and it was clear they needed to do whatever was available. I didn’t have much lung involvement at all back then, so I was spared the mist tents and the beatings. I did deal with a lot of gastrointestinal issues though, and I do remember fighting with my parents about taking pancreatic enzymes. They were horrible back then. They smelled like cow poop — yes, seriously — and didn’t really work for me, so I protested vehemently.”

“I think I can guess how it might feel to be a parent of a kid with CF who argues about treatments,” Desch said. “Although my two sons are now remarkably healthy, I have dealt with my fair share of parental-child arguments over taking medicines, doing rehabilitation exercises after surgery, etc., so I know how frustrating that is. They have never been life-threatening issues, though, so maybe I am kidding myself. It must be incredibly stressful to know what your kid needs to do to maximize the chances of staying alive and out of the hospital, and having them either not understand, or worse, not care.

“Anybody who has either been an adolescent, or raised one, knows they often believe their parents are completely out of touch with reality,” Desch said. “At this point, they ‘know better’ and often stop listening to advice about healthcare (along with everything else). This is why so many kids fall off in their lung function during the transition years from pediatric to adult healthcare teams. It is frustrating, no doubt, and I am so grateful that my kids are healthy.”

Umberger clearly recalls this battle with her parents.

“I just wanted to be normal — I didn’t want to take pills, inhale medicine or have my mom give me manual airway clearance. At the age of 14, I started to rebel,” Umberger said. “I would grab my pills, but would always take them. In the summer when I was sick and needed antibiotics, I would wait as long as possible. I didn’t want them because they were sun-sensitive and I wanted to go to the pool with my friends. The normal things like sleepovers, vacations, and playing outside in the snow were anything but normal because they required lots of planning to make them happen. Now that I am an adult, those things are equally hard — planning vacations with sunshine is hard because of the uncertainty of feeling well enough or being on antibiotics.”

Tara agreed. “Treatment schedule certainly affects my son’s life drastically. His free time for play is severely limited. We try to accommodate as much as we can by setting up his vest and nebulizers where we can play with blocks or PlayDough and use the time well. We also have to focus on having our family time during his treatments …

“We are gearing up to homeschool so that we can use the treatment time to do school and maximize play and free time without spending all of his free time at school and then only having time for treatments and sleep at home,” she said.

“My son hasn’t fought his treatments much,” Tara said. “He still doesn’t grasp that this isn’t totally normal. We treat it as matter-of-fact, just like you go to the bathroom when your body needs it, and you sleep when your body needs it, and you eat when your body needs it, likewise we do nebs and vests at these times because your body needs it. Right now he is young enough that he has just enjoyed the attention, but he is not yet aware of how this is different from his peers, and he isn’t yet old enough that it cuts into his opportunities to play with other kids. That will be really hard.”

As for the monotony and the “this is forever” feeling, “Well, it IS forever, until it’s not anymore,” Desch said. “I am living many, many years past what many say was my expiration date. With every birthday that I am still here, I am more grateful for the treatments and less annoyed by them. I suppose that is natural. If I were younger, and saw the pipeline of all these new drugs, I would be completely impatient for that ‘magic pill’ that was going to shorten my treatment burden. Then, my daily vest sessions and nebs would be more monotonous than I currently perceive them to be.”

“I feel like everyone has something, and CF is my something,” Umberger said. “There are days I would do anything to not have to do anything. I understand that doing nothing will not allow the rest of my life to occur. My mindset was not always that way. In college, I would take those days and not do any medicine and go do whatever I wanted. Now on those days I reward myself with something little if I get my pills, inhaled meds, airway clearance, and exercise in. It helps to have good support, too.”

Tara said it’s been difficult, “as a parent, to talk with our friends and acquaintances because most of them don’t realize the details of CF. We take vest, pills, and a packed meal with us to church, and keep his treatment schedule during his time in Sunday School, and the other parents and teachers often ask how soon my son will grow out of this, how much longer we need to keep doing treatments. It’s so hard to, in front of my son and all his friends, answer truthfully, ‘until he dies,’ without it sounding terrible, and actually, because CF is progressive, his need for vests and nebs will only increase from here, not decrease.

“But when we are home as a family, we have already flipped our perspective on what days in our lives look like and what our plans are for the upcoming years,” Tara said, “so the monotony doesn’t really haunt me. I certainly understand how others, with different family situations, different personalities, really have a hard time with this, though.”

On fitting cystic fibrosis treatment into workday demands or other busy schedules, Umberger said that living life with CF makes you a constant planner.

“My husband is always giving me a hard time,” she said. “As a CFer, we need to plan our whole day because there are sooo … many things that have to occur. We have things that have to get done to breathe, digest food, and monitor blood sugar. On a good day everything gets done, but when things don’t get done you start to cut things. I need to get my airway clearance and medicine done, so now I can’t go out to dinner with friends. It is even hard to make plans with friends a week away because you don’t know how you will feel. It is a constant battle of choosing to live or have a life with fun.”

“Fitting it in is brutal,” Tara agreed. “If you think of your workday or a day of homelife or kidlife or whatever the situation, and then try to fit in taking care of CF, there is no way to have enough hours in a day. If you think of taking care of CF, and then try to fit in a workday, it is exhausting, and feels like the whole family is a slave to CF, or life inherently revolves around that person and they are owned by CF.

“What works for us is to first schedule the treatments, set realistic expectations for what else we can fit in, and then focus on the fact that this is what we need to do as a family to take care of all of us, instead of seeing it as specifically my son’s needs, or his disease …

“It can also seem bizarre to others,” Tara continued. “I have, more than once, sent an email at 5:15 a.m. to let someone know that I’m sorry, but things are running too behind and I will not be able to make it to our 10 a.m. meeting that day. But when morning routine takes five hours, that’s how life is. I’m much more satisfied coming from the perspective of ‘deciding about our day’ than looking at it as a choice between treatments and activities. That is, if you see yourself as choosing which items to do, there is not enough time and you are indeed choosing between them. But if you see yourself as planning out your day, then the choices feel less like sacrificing opportunities vs. health, and more like being in control.

“My husband and I both work full time,” Tara said. “Both of our workplaces are very family-supportive, and prioritizing our son over a given meeting or whatever is fully supported. We both have flexible hours and are able to do some work from home. We have a part-time nanny, and both my mother and my husband’s mother also help with [my son’s] care, covering one to three workdays every week. Thus, we are able to both get in our hours each week, but this regularly includes weekends. There isn’t a daycare option that could accommodate my son’s treatments that we could afford in our area.”

Desch talked about her one-hour commute. “To make it easier for me to do my morning treatment and get to work on time,I had been doing nebs in the car while driving — not really safe because having a coughing spasm while driving on a freeway is not recommended,” she said. “The amount of grief I got from making this request would astonish you. Of course, there are laws that one can resort to, if you want to make it an issue. But from the description of the treatment regimen, you can see how hard it might be to fit an eight-hour job plus the commute in each day.”

“The same is true for social events,” Desch said. “It’s tough to stay out when you are having fun, knowing that you have a treatment to do before you can hit the pillow. Sometimes, I admit, I get annoyed when other people don’t understand, and staying up to watch the end of a movie is no big deal to them, but to me it puts my bedtime off to almost midnight.”

On the issue of privacy, Umberger said she used to being very private about her cystic fibrosis. She said that if someone asked about her cough, she would attribute it to allergies or a cold.

“Now that I have more self-acceptance I am a little more open,” Umberger said. “I have a personal training business. I find my openness with my clients makes them more motivated. They always say, if you can do two hours of medicine and therapy a day and work out, I can do a 30-minute workout. It is hard admitting you just can’t do something. For example, when it is cold outside, I can’t walk too far without coughing to the point of throwing up. It took me five years of this before I asked my doctor for a temporary handicap parking pass. I didn’t want to be judged, but I realized I was the one judging myself.”

“I was very closeted about my CF until I was in college,” Desch said. “I hoped other people didn’t know, but growing up in a small town in a family with three of seven kids with CF, this was kind of crazy. I just didn’t talk about it. Fortunately, other than my GI issues, I didn’t really have to explain much. I wasn’t sick that much, never was hospitalized, and didn’t do treatments. It’s easy to say in the closet in that scenario.

“If I were a teenager today, of course that wouldn’t really be possible,” Desch said. “Treatments would get in the way of life, and it would be tough to keep it all under wraps. It’s tough to be a teen with CF. You already are super self-conscious, because all teens are, and then there is this cough, and funny-looking nails, and school absences to explain. I know of a few adults who are very quiet about their CF. They don’t participate in Facebook groups or other forums. They just deal with it and try to live their lives as normally as possible. I frankly don’t know how they do it.

“I find great strength in talking with others with CF,” Desch said. “Only people who live with it really get it. But everybody has different coping mechanisms. At different points in my life, I think I’ve used all of them, including denial.”

Tara said her family is “very open” about her son’s cystic fibrosis, “and I cannot fathom how we would keep my son’s CF a secret without having a full-time stay-at-home parent in addition to our childcare, removing ourselves from church and all other regular social activities, and never attending any function or gathering or visiting family unless the entire event would take less than two hours. Admittedly, we are sticking to a proactive schedule of treatments, instead of just the minimum to keep alive.”

Finally, on the isolation imposed by the exigencies and time demands of cystic fibrosis therapy regimes, Desch said she gets a lot of reading done.

“I sit in my chair hooked up for hours every day,” she said. “If my back hurts — and it often does — I stand and walk slowly on my treadmill while I do my treatment. It can be lonely, for sure, so I try to occupy myself. The only time I have ever had percussion therapy from a real live person is in the hospital. I will admit, I do like it better than the vest, but the vest is way more convenient.”

“I have two dogs that keep me company during therapy,” Umberger said. “I have been using exercise for the past five years for airway clearance. I use a Polar Heart Rate watch to monitor my intensity. I do circuit training, which combines strength and cardio. I do 30, 45, or 60 seconds of cardio exercise, getting my heart rate to 140-160. At this heart rate I usually will cough, clearing my lungs. I also will rotate in interval running, 60-90 seconds of running, and 90-120 seconds of rest. I also use vest time to grade papers or for Facebook time.”

“I have two dogs that keep me company during therapy,” Umberger said. “I have been using exercise for the past five years for airway clearance. I use a Polar Heart Rate watch to monitor my intensity. I do circuit training, which combines strength and cardio. I do 30, 45, or 60 seconds of cardio exercise, getting my heart rate to 140-160. At this heart rate I usually will cough, clearing my lungs. I also will rotate in interval running, 60-90 seconds of running, and 90-120 seconds of rest. I also use vest time to grade papers or for Facebook time.”

“We try to make the therapy confining without being isolating,” Tara said about her son. “We plan for that to be our time to play with blocks or to draw together or to read together. However, my son is still using the pediatric mask for his nebulizer treatments. As soon as he switches to the adult mouthpiece, he will be much more strictly confined during nebulizer treatments, and no longer able to talk at all.

“We already had some familiarity with ASL [American Sign Language], so we are trying to keep learning ASL as a family (but that’s certainly not a realistic option for most families, and I don’t know that we will really succeed at it, just aiming for better than nothing). I love the current technology, in terms of the Internet. I know that screen time should be limited for kids, but if we can use a treatment to actually find pictures or watch a documentary answering my son’s current random questions about what hedgehogs eat or how a didgeridoo is made, then we consider that interactive time and learning opportunities. As my son gets older, I picture us using treatment time for school, as I mentioned earlier, and would like to combat some of the isolation with Skype friends and so on.”

The CysticLife Community Driven Research Fund community is now crowdfunding the exercise therapy research project on Althea Health’s Social Funds platform with the Unleashus Campaign.

Althea Health is a Silicon Valley startup dedicated to helping rare disease patient advocacy organizations raise funds and conduct research. The company’s vision is to accelerate new therapies and cures for rare diseases by leveraging digital technology and the social capital of the patients and families affected by these diseases, with a specialized platform designed to facilitate rare disease communities reaching reach their social networks.

“Our mission is to empower patient communities,” said Althea Health CEO Manu Kodiyan. “We are excited to be partnering with CysticLife and researchers at the Mayo Clinic to enable patients to conduct research that matters to them and allow cystic fibrosis patients to contribute to this study from anywhere in the country.”

“[Donors] have the opportunity to fund a study that would help researchers learn what types of exercise are effective,” observed CysticLife.org’s Ronnie Sharpe.

CysticLife has also announced their partnership with the Sharktank Research Foundation (SRF), a nonprofit medical research organization dedicated to accelerating development of safer and more effective therapies for cystic fibrosis.

CysticLife has also announced their partnership with the Sharktank Research Foundation (SRF), a nonprofit medical research organization dedicated to accelerating development of safer and more effective therapies for cystic fibrosis.

CysticLife says this partnership is important in a number of ways, first because it will allow SRF to act as a fiscal agent for CysticLife as they prepare to crowdsource the funds necessary to support community-driven research. This means that the contributions to the research project will be treated as donations and be tax deductible. Secondly, the SRF has established relationships around the country with cystic fibrosis researchers that are also interested in becoming involved and supporting community-driven research.