Diversity, composition of bacteria in gut altered in CF adults: Study

Increase in harmful bacteria tied to poor nutritional status in patients

Written by |

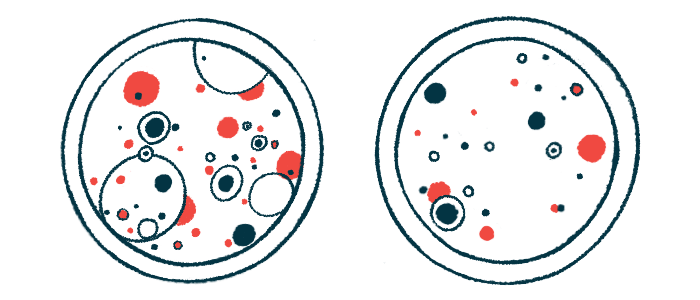

The diversity and composition of bacteria in the gut of adults with cystic fibrosis (CF) differed significantly from that of these patients’ non-CF counterparts in a new study, data revealed.

Further, poor nutritional status and certain mutations in the CFTR gene, the underlying cause of CF — and which lead to more severe disease — were linked to an increase in the abundance of harmful gut bacteria and a decrease in beneficial bacteria.

“Undernourished CF patients showed significantly lower [bacterial] diversity compared to [the] non-CF group and CF patients with BMI [body mass index] within the norm,” the researchers wrote, adding that this study “provides valuable insights into the intricate interplay between microbial dynamics, CFTR mutations, and nutritional status.”

“The identified associations pave the way for future studies exploring targeted treatment to modulate the gut microbiota and improve clinical outcomes in CF patients,” the team wrote.

The study, “Gut microbiota in adults with cystic fibrosis: Implications for the severity of the CFTR gene mutation and nutritional status,” was published in the Journal of Cystic Fibrosis.

Investigating the role of gut bacteria in CF

In CF, mutations in the CFTR gene disrupt the production and/or function of the CFTR protein, which normally helps maintain sufficient fluid on the surface of tissues. A lack of functional CFTR protein reduces surface hydration, leading to the accumulation of sticky mucus in various organs, including the lungs and digestive tract. CFTR mutations have been categorized into different classes based on the specific defect in the protein’s production or function.

Thickened mucus in the digestive tract can cause complications such as pancreatic insufficiency, intestinal inflammation, pain, slower movement of digested food, intestinal blockages, reduced nutrient absorption, and constipation.

Such intestinal changes can alter the gut microbiome, or the community of bacteria, fungi, and viruses that colonize the gastrointestinal tract and play a role in immune function, metabolism, and other processes.

A recent study showed that the microbiome of CF infants was affected by age, geography, and antibiotic use.

In this new study, scientists in Poland examined the gut microbiome in adults with and without CF and its relationship to the severity of CFTR mutations and nutritional status.

Eligible CF patients were clinically stable, had received no antibiotics in the two months before the study, and were free of lung exacerbations or intestinal symptoms during the previous four weeks. No participants were receiving CFTR modulator therapy, used to treat patients with specific types of disease-causing mutations.

DNA was extracted and analyzed from stool samples collected from 41 adults with CF and 26 non-CF individuals, who served as controls. Bacteria were identified at the genus level, or groups of closely related bacteria species.

Nutritional status was assessed by body mass index, known as BMI, a measure of body fat based on height and weight. A normal BMI ranges from 18.5 to 24.9 kg per square meters (kg/m2).

Underweight CF patients found to have more harmful gut bacteria

In adults with CF, the richness of their gut bacteria, or the abundance of different genus groups, was significantly lower than in non-CF controls, emphasizing “the significant impact of the disease on the gut microbiota composition,” the researchers wrote.

The bacterial diversity within samples from CF patients, or alpha diversity, differed significantly from samples from the control group. However, there were no differences in microbial diversity within CF samples according to the severity of the CFTR mutation.

When patients were compared by nutritional status, those considered underweight, with a BMI less than 18.5, had significantly lower diversity within their samples than CF patients with a normal BMI and controls. Similar significant differences were found in other measures of genus richness and evenness.

The microbial diversity between samples from different groups, or beta diversity, also showed significant differences. Still, there was no significant difference in bacterial communities between the CF groups based on the severity of the CFTR mutation. In this analysis, however, there were significant differences between controls and CF patients with low or normal BMI values.

The correlation between the abundance of these genera and the severity of CFTR mutations adds granularity to our understanding of how genetic factors influence the gut microbiota landscape.

Two groups of beneficial gut bacteria were less abundant in CF patients than in controls: Faecalibacterium (13.9% vs. 47.9%) and Blautia (5% vs. 19.7%). In comparison, two types of harmful bacteria were more abundant in patients than controls: Bacteroides (37.8% vs. 5.3%) and Streptococcus (17.8% vs. 0.5%).

With more severe CFTR mutations, the relative abundance of Faecalibacterium and Blautia decreased significantly, while the relative abundance of Bacteroides and Streptococcus increased significantly.

“The correlation between the abundance of these genera and the severity of CFTR mutations adds granularity to our understanding of how genetic factors influence the gut microbiota landscape,” the scientists noted.

Likewise, underweight CF patients had the highest abundance of Bacteroides and Streptococcus and the lowest abundance of Faecalibacterium and Blautia.

Microbiome research is expected to evolve as scientists look for ways to better treat the disease.

“Continued investigations will probably reveal additional factors in the intricate relationship between CF and the gut microbiota, offering new possibilities for personalized therapeutic strategies,” the authors concluded.