Successful transplant reported in CF patient with heart problems

More research needed into 'seemingly rare manifestation,' said scientists

A young man with cystic fibrosis (CF) successfully underwent a heart transplant, according to a first-of-its kind report described by researchers, who said the man’s heart issues arose as a rare complication of CF itself.

The patient’s experience was described in the paper, “Isolated heart transplantation in an adolescent with cystic fibrosis—A case report,” which was published in Pediatric Pulmonology.

CF is caused by mutations in the gene that provides instructions to make the CFTR protein. Defective or no CFTR leads to an abnormally thick mucus being produced that builds up in organs, especially the lungs and digestive tract, driving most of the disease’s symptoms.

Compared with the lungs and pancreas, the heart isn’t usually much affected by CF, so doctors generally don’t look for problems except in extreme cases. The CFTR protein is expressed by heart cells, however, and data from animal studies suggests CFTR dysfunction can lead to heart abnormalities, so heart problems in CF might be more common than believed, underscoring the need for more research into this seemingly rare disease manifestation, the scientists said.

There have been reports of CF patients with irregular heart rhythms, called arrhythmia, but there’s never before been a report of someone with CF who had heart disease severe enough to need a heart transplant.

Early signs of heart problems

Doctors first noticed the patient was experiencing arrhythmia when he was 9 years old. He also had a cough and shortness of breath, and was underweight for his age — all common symptoms of CF that arise due to thick mucus in the lungs and digestive system.

A heart exam showed the boy was having left heart failure, meaning the left side of his heart, which is responsible for pumping oxygen-rich blood out to tissues, wasn’t functioning well enough to meet the body’s needs.

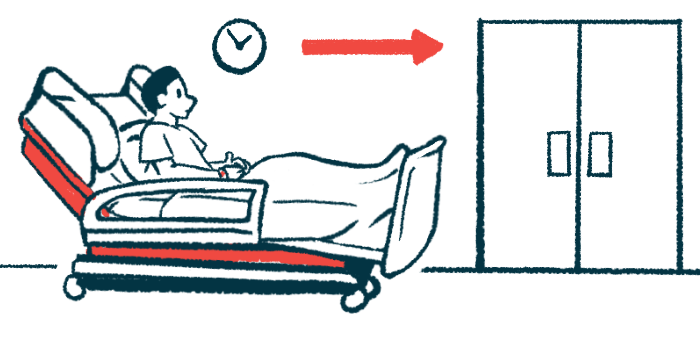

Neither medicines nor a defibrillator implanted in the patient’s chest improved his heart function, so a heart transplant was decided on. Although the boy’s heart function was a serious concern, measures of lung function were within ranges considered normal for someone who doesn’t have CF.

The heart transplant was successfully performed when the patient was 12. An analysis of his explanted heart showed signs of scarring in the heart muscle and enlargement of the left ventricle.

In the years after the heart transplant, the patient had a number of complex bacterial lung infections and his lung function worsened. Lung infections are a common problem in CF and the youth was likely more vulnerable to them because he needed immune-suppressing therapy to reduce the risk of rejecting the transplanted heart.

When the patient was 22, he started treatment with Trikafta (ivacaftor, tezacaftor, and elexacaftor), a triple-combination medicine that works to boost the functionality of the defective CFTR protein in patients who carry certain mutations. In one of his CFTR gene copies, this patient carried the F508del mutation, the most common CF-causing mutation, which does respond to Trikafta.

The patient was 24 at his latest follow-up. His lung function had improved notably since starting Trikafta and he had fewer exacerbations, which are periods of acute worsening of lung symptoms, but he was still underweight.

Heart transplant “may be feasible in [people with] CF even though infections play an important role and are fostered by immunosuppression after transplantation,” wrote the researchers, who noted that Trikafta “seems to be safe in post‐transplant patients.“